Social work values can take on toxic management cultures

Public inquiries into high profile organisational failures – including the Post Office, the infected blood scandal, Grenfell, Thirlwall, Mid Staffs NHS Trust – highlight the need for a radical new approach to public policy and senior leadership in our major institutions.

The disastrous part-privatisation of probation, the impact of contracted-out accommodation services for looked-after children, and the crisis in higher education similarly indicate that something is badly wrong.

I was recently part of an international group of academics and colleagues working on an EU-funded project to provide materials for healthcare professionals to support service users experiencing domestic violence and abuse across Europe.

We recognised that behaviour within organisations can mirror coercive control, which has traumatic consequences for individuals. Having experienced abusive and toxic behaviour within organisations ourselves, including in public services and universities, we decided to act. And so our next project was born.

In the UK, in an intimate or family relationship, coercive control is now a criminal offence, yet these behaviours are often perpetrated in organisations with little consequence.

Our group now incorporates colleagues with expertise in compassion-focused approaches and includes members from the UK, Iceland and Sweden.

Together we have academic and professional experience in psychology, psychotherapy, social work, nursing, senior leadership, human resource management and research. We have developed a leadership model called ECHO (Ethical, Compassionate, Humane Organisations), with the following aims:

- To identify the socio-economic, structural and psychological mechanisms which underpin organisational failure and can lead to tragedy

- To construct a model of leadership to develop insight and understanding, promoting safety and wellbeing through ethical, compassionate and humane leadership practice

- To provide practical interventions for leaders in the form of training and development, mentoring and applied research, supporting a whole organisation approach based on ECHO principles

Socio-economic, psychological and structural influences

Neoliberalism and managerialism can narrow the focus of leaders, detract from the values and ethics of their profession and divert attention from public safety.

Neoliberalism has seen exploitation of public services for financial gain, de-regulation and undermining of state provision for ideological reasons, fragmenting provision in pursuit of ‘more for less’ and lowering standards of care.

Managerialism focuses primarily on the objectives of the business model; numerical, reductionist targets support competition and aim to maximise profits, risking perverse incentives and distraction from professional standards.

Emboldened by managerialism and neoliberalism, some politicians and senior leaders also display hubris, defined by leadership experts Ben Laker, David Cobb and Rita Trehan in Too Proud to Lead as “no prisoners taken, lack of care for others, fierce defence of reputation and power and, above all, defiant and dangerous self-interest”.

It’s a chilling description demonstrated in global politics and nearer to home, for example, in the behaviour of senior executives in the Post Office Inquiry.

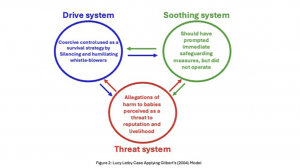

Psychologist Paul Gilbert’s evolutionary model /affect regulation system illustrates how behaviour can be influenced by external factors:

The threat (red), drive (blue) and soothing (green) systems need to be in balance for a healthy life. Imbalance occurs in organisations when the ‘threat’ system of senior leaders becomes over-developed and focused on self-protection as a response to fear of failure, loss of reputation or livelihood.

The ‘drive and resource seeking’ system then becomes narrowly focused on survival, with potential for moral injury and marginalisation of employees and negative impact upon users of services and communities. Consequently, the soothing system, which should minimise harm, hardly applies, increasing the potential for tragedies to occur.

The ECHO model

To reverse the imbalance identified by Gilbert, ECHO incorporates three components into our leadership model:

Compassion

Gilbert defines compassion as “a sensitivity to suffering of self and others, with a commitment to try to alleviate and prevent it”.

Far from implying ‘soft’ or weak leadership, compassion requires the wisdom and courage to overcome fears and address the ‘hard’ problems we face as a society.

Our model allows for leaders first to recognise suffering in themselves, for example, through the immense demands and complexities they face daily and relentless pressure to meet performance targets which can disconnect from personal and professional values.

Encouraging leaders to acknowledge these influences and explore mechanisms which can support them can lead to recognition of suffering in others and action to alleviate it.

Applying models from safeguarding practice

Just as mechanisms such as critical reflection and analysis and professional curiosity have improved safeguarding practice in social work, we will apply them to leadership to improve public safety.

Studying the outcomes of public inquiries in social work has led to innovations in policy and practice, so we will similarly review public inquiries into organisational failure, enabling leaders to reflect on and improve their practice, including strategies to address ‘hard’ problems.

An example of ethical, compassionate, humane leadership

A successful example of using compassion to address ‘hard problems’ is the London Mayor’s Charter concerning school inclusion and violence reduction. This is a courageous and wise initiative, which has reduced knife crime and school exclusions by employing strong boundaries and clear expectations alongside relationship-based approaches and measures to alleviate the effects of poverty.

The ECHO model applied to the Lucy Letby* case

This analysis considers what factors could have prompted senior managers at the Countess of Chester Hospital – who could now face charges of corporate manslaughter – to react defensively to the possibility that a nurse may have been harming babies in a neonatal ward. It illustrates how applying professional curiosity and critical reflection and analysis to leadership decision-making might have prioritised safeguarding:

Senior managers were described as seemingly ‘in denial’ and operating a bullying culture; whistleblowers were instructed to write an apology to Lucy Letby and stop making allegations against her. Concerns were first raised in 2015, yet the police were not called in to investigate until 2017. Letby continued to work on the unit for much of this time and was never suspended.

- Gilbert’s model illustrates how perceived threats could have caused leaders to adopt self-protection strategies, pushing the drive system into survival mode through coercive measures such as silencing and humiliation of whistleblowers. The soothing system, which should have prompted immediate action to protect babies from harm, did not operate.

- The paramount consideration should have been to protect children by removing Letby from the unit and calling the police. Professional curiosity could have prompted safe uncertainty and allowed leaders to question their assumptions, consider different perspectives, identify who was most at risk and recognise what they could not hear and see, clarifying what action should be taken.

- Critical reflection and analysis using, for example, social work professor Jan Fook’s reflective model which analyses power relationships, could help to identify hubris, change the narrative and highlight the need to protect the most vulnerable.

A new vision for leadership

ECHO’s unique contribution lies in the practical application of an interactive training, development and applied research initiative for senior leaders.

ECHO is placed within a systemic context, recognising a wide range of influences upon organisations. Importantly, we aim to engage with and influence policymakers; working with leaders alone will have little impact if narrowly defined and punitive performance frameworks which can trigger self-protection continue to dominate.

In the current political context, where league tables in the NHS and the prospect of criminal sanctions against professionals who fail to report child sexual abuse can drive leaders into survival mode, the risk of perverse incentives and unintended consequences remains.

It has never been more vital for senior leaders in public services to acquire deeper understanding of the mechanisms which can distract and result in tragedy. ECHO will provide the developmental support and guidance for this to happen.

*The Lucy Letby case has been used as an example purely to illustrate how the behaviour of senior executives could have been influenced by fears about reputation and threats to their positions, rather than by the imperative to safeguard children, when faced with the possibility that a nurse may be harming babies. It is not intended to contribute to the current debate about the validity of scientific evidence in this case.

Kath Morris is a semi-retired social work academic, former probation senior manager and coordinator of ECHO. She is keen to hear from senior leaders in social work and allied professions interested in piloting the ECHO model. Email kathmorris100@live.co.uk or phone 07807 466090