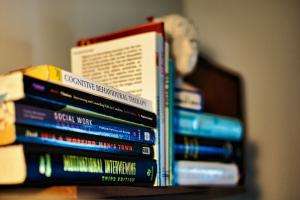

CBT, me and social work

Published by Professional Social Work magazine, 15 June, 2022

It was a freezing November day when I left my house for a bike ride along the canal. I needed to get out to clear my head, but also to reflect on where I was at and what I needed to do.

I had been off work which affected my mental health, increased sleep issues and was impacting on my relationship with my nearest and dearest. As I cycled in the cold, I gathered my thoughts and recognised for the first time in my life that my deteriorating mental health was not something I could manage on my own.

Although my time off work may have been the catalyst to the crisis in which I found myself, this became less important than what the negative thoughts and feelings it triggered. Support from a BASW professional officer also helped to retain my sense of perspective and value of myself as a credible person and practitioner.

I referred myself for counselling. Over a period of eight weeks my counsellor listened attentively, drawing links and patterns from the information shared, and provided me with the tool of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT).

Together, we were able to identify what was driving my lack of confidence, leading me to deal with my past issues. Talking enabled me to identify patterns, including negative thoughts stemming from insecurities as a child, attributed in part from my own parent’s tense relationship towards each other and my experiences of being bullied as a child and adult.

These had contributed to negative thoughts about self that had developed over time.

I was tasked with completing a thought record for identifying unhelpful thoughts and reframing these positively. This nurtured a shift from unhelpful thoughts about self to building my self-esteem in the present and a hopeful future.

Being able to test the tool and apply to home and work situations helped me to see the difference between the reality and my perception of the situation.

Having gone through this often painful yet thought-provoking journey and returning to social work practice with a new team helped regain my confidence in self and my sense of value as a social work practitioner, educator and best interest assessor. Also as a husband, dad, family member and friend.

The experience has made me reflect on how CBT may help service users think in a strengths-based way.

I have been able to apply my learning of CBT in my social work practice. One example is a service user with learning disabilities who responded initially with anger when discussing managing finances which triggered negative thoughts around previous debt.

Reframing the conversation helped them question their own negative perception of the situation, which included a wrong expectation of controls placed on them, and reframe it positively.

Such an approach is not unfamiliar in social work and CBT shares similarities with solution-focused practice and motivational interviewing, as favoured by the Frontline training scheme for children and families social workers in England.

When applying them we must be careful not to ‘problemise’ the person and recognise that psychology is impacted by environment and structural inequalities that impact on people.

But having experienced the benefits of CBT in my personal life I believe a knowledge of this approach has much to offer in our practice helping people to move forward in their lives.

Below are two perspectives about the benefits and limits of CBT in social work from a theoretical perspective. The first is from my counsellor Pieter Vroom and the other from social work educator and trainer Siobhan Maclean.

Pieter's view

CBT identifies four areas in our lives: cognitions, behaviours, emotions and the physical. All four are interlinked and influence one another. The focus of CBT is on cognitions and behaviours, as these are more easily accessible. It encourages clients to reflect on behaviours and thinking patterns and modify them if they are found to be unhelpful or unrealistic.

It will encourage useful behaviours like exercise and constructive activities, but most work will usually be done in the area of our thinking. The way we feel about events happening in our lives strongly depends on how we think about them.

When CBT talks about cognitions or thinking it does not refer to long, complicated thought processes, but rather the quick thoughts, that sometimes we might not even be aware of, that interpret the things that are happening.

If we have developed thinking habits that are overly critical or negative, we will start to feel negative about things and events that in and of themselves are not.

A first step will often be to try and identify unhelpful thinking habits, like catastrophising or black and white thinking. Once we are aware of them, we can start to challenge these ways of thinking when they occur. This needs to be an ongoing process that will gradually change these thinking habits. Habits don’t change overnight.

CBT is a very pragmatic and practical therapy, very much rooted in the here and now, which is both a strength and a weakness. It will not address issues that might have occurred in the past and have an influence on how we feel in the present, like some other types of therapy will.

There is a strong evidence base that suggests CBT is particularly useful for clients with depression and/or anxiety and that it can be effective in a relatively short number of sessions.

Siobhan's view

As social workers we draw on a range of ideas to influence our practice, many of which are drawn out of counselling and therapy. In my writing and training about theory and practice I often refer to some of the ideas that we draw from these areas, but I think it is important that we recognise the skill base of counsellors and the training which they have had.

If I asked a student about their use of theory, I do not want them to say: “I used CBT”, because they are not specifically trained in its use. However, I think it is perfectly legitimate for them to say: “I drew on an understanding from my knowledge of CBT.”

The link that CBT suggests between our thoughts, feelings and actions can be particularly helpful for us to understand as social workers. For example, when considering our use of self, then understanding the links between what we feel, think and do can be helpful.

*Name changed to protect identit