Preparation for Module 2: (1 hour)

Reading

Dominelli, L. (2020) ‘A green social work perspective on social work in the times of Covid-19’, International Journal of Social Welfare.

Consider while reading

- What challenges did social workers face during the Covid-19 pandemic?

- What are some of the ways that social workers overcame these challenges?

- How do wider contexts shape social work during disasters?

Learning goals

Following this module you should be able to:

- Explain legislation, policy and procedures that are pertinent to the context.

- Promote the importance of the social work role in and advocate for the highest quality social work services for people before, during and after a disaster.

- Reflect on the wider contexts, causes and implications of a disaster.

Full details on the learning goals on which this, and other modules in this series, are based, can be found via the Social Work in Disasters overview page. You can also find an assistive glossary on this page we recommend you refer to.

Module 2

Disasters and the law introduction

Complete short task 1 in workbook (15 minutes)

The governance of social workers during a crisis situation is devolved to individual local authorities. During a disaster, the legal rights that individuals have persist. For example, under section 47 of the Children Act 1989, a local authority must still investigate if there is reasonable cause to suspect a child is experiencing, or is likely to experience, significant harm. Following a disaster, this duty, and other legal duties, can become significantly more complex to meet. Consider the following example:

Lucy is a 6 year old child who lives with her parents Sarah and Rick. Following an incident where Rick was accused of breaking Lucy’s arm while under the influence of alcohol, an Emergency Protection Order was put in place that includes an exclusion preventing Rick from being at the family home while an investigation takes place. Rick is now staying at a friend’s house a few streets away. Severe and unexpected flooding has now hit the area, requiring the evacuation of Rick, Sarah and Lucy, who are all told to go to the local community centre where beds and food are being provided.

Reflection questions:

- What would be risks in this case? How could a social worker respond to these?

Additional legislation

Some additional legislation to consider/be aware of (follow the links for more information):

- Housing Act 1996

A person who is homeless or threatened homeless as a result of a disaster shall be considered a priority need for accommodation (Section 189) - Housing Act 2004

Chapter 3 gives powers of “emergency remedial action” if a category 1 hazard (fire, gas leak, structural collapse) creates an imminent risk of serious harm to the health and safety of the occupiers of residential property. - Humanitarian Assistance Lead Officer (HALO)

Specific to London under the London Resilience Partnership, the HALO is appointed by local authorities and is typically the Director of Adult Social Services. The role involves bringing together partners in health, the police and voluntary sectors to oversee humanitarian assistance efforts. - Family Liaison Officer (FLO)

A Family Liaison Officer is a police investigator who provides support and information to families in the event of a crime or disaster. While their role involves providing this support in a sensitive and compassionate manner, their primary role is to gather information and contribute to the investigation of an incident. Therefore, they are not a replacement for social work and other supportive interventions. - Body Identification/Viewing Procedures

There are specific procedures around the identification of bodies and the use of mortuaries following a disaster/emergency. Social workers will often be involved in supporting individuals and families through these processes, and they should be included in resilience plans.

Find more details about these processes.

Civil Contingencies Act 2004

Potentially the most important piece of legislation for working in disasters is the Civil Contingencies Act 2004, which was introduced in the UK following the Foot and Mouth outbreak in 2001 to provide a coherent framework to responding to large scale events like this. The term disaster does not appear in the legislation at all, and instead the term emergency is used, which is defined as:

- an event or situation which threatens serious damage to human welfare in a place in the United Kingdom,

- an event or situation which threatens serious damage to the environment of a place in the United Kingdom, or

- war, or terrorism, which threatens serious damage to the security of the United Kingdom.

Complete short task 2 in workbook (10 minutes)

The Civil Contingencies Act requires the creation of Local Resilience Forums, multi-agency partnerships for planning emergency response. It also created a distinction between two types of responders, Category 1 (core responders) and Category 2 (co-operating responders). The below table highlights some key organisations in each category.

Take a look at the more comprehensive list

Category 1

- Local Authorities

- NHS

- Police Forces

- Transport Police

- Ambulance Services

- Environment Agency

Category 2

- Network Rail

- London Underground

- Airport operators

- Telephone Service Providers

- Electric/Gas distributors

- Water/Sewerage undertakers

Complete short task 3 in workbook (10 minutes)

Category 1 responders must:

- assess the risk of emergencies occurring and use this to inform contingency planning

- put in place emergency plans

- put in place business continuity management arrangements

- put in place arrangements to make information available to the public about civil protection matters and maintain arrangements to warn, inform and advise the public in the event of an emergency

- share information with other local responders to enhance co-ordination

- co-operate with other local responders to enhance co-ordination and efficiency

- provide advice and assistance to businesses and voluntary organisations about business continuity management (local authorities only)

- have an appropriate number of trained emergency response personnel to respond to disasters

Category 2 responders do not have the same duties as Category 1 responders, but must co-operate and share information in the event of an emergency.

The Civil Contingencies Act 2004 gives the government the power, in the event of a catastrophic emergency, to amend or suspend any legislation except the Civil Contingencies Act itself, and the Human Rights Act 1998. Therefore, when working in disasters, a human rights based approach to working becomes all the more important for social workers. Important human rights that you need to be aware of in working in disasters include, but are not limited to:

- Article 2: Right to Life

- Article 3: Freedom from torture and inhuman or degrading treatment

- Article 5: Right to liberty and security

- Article 6: Right to a fair trial

- Article 7: Respect for private and family life

- Article 10: Freedom of expression

- Article 11: Freedom of assembly

In the event of a major disaster whereby the Civil Contingencies Act 2004 is used to suspend other pieces of legislation, social workers having in depth knowledge of human rights, and having the confidence to use these in advocating for others, will be vital.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the government introduce the Coronavirus Act 2020. This provided local authorities with the option, under very specific circumstances, to suspend many of their adult social care duties, as well as altering some aspects of the Mental Health Act 1983. The Adoption and Children (Coronavirus) (Amendment) Regulations 2020 (widely known as Statutory Instrument 445) were also introduced temporarily suspending several legal protections related to looked after children. However, it is notable that neither of these were implemented under the provision of the Civil Contingencies Act 2004.

Reflection question

- Did either of these legal changes during the Covid-19 pandemic impact on your own work?

If not, click on the link for the one most relevant to your work and consider the implications of the legal changes that were implemented.

Advocating for the role of social workers in disasters

A 2008 Social Care Institute for Excellence report suggested that social care should be involved in Local Resilience Forums, and local authorities are listed as Category 1 responders under the Civil Contingencies Act 2004. However, in practice social workers are rarely involved in emergency planning and preparation within the UK. Despite their relative invisibility in many disasters, social workers have long held multiple crucial roles in disaster response and recovery. This includes the example of social workers supporting “shell-shocked” soldiers returning from the First World War (more likely to be termed post-traumatic stress disorder today).

However, the role of the social worker following disasters is not well understood by the public, other professionals and many social workers. This creates a significant barrier for social workers working in these contexts. Social workers responding to recent disasters have shared stories of visiting the scene of a disaster and struggling to articulate their role, including following the Grenfell Tower Fire and the numerous UK terrorist attacks in 2017. People impacted by disasters have similarly expressed their confusion about the support social workers can provide within these contexts. This has been shown to impact on the trust that social workers are able to develop with those impacted.

Watch the video resource of Margaret Aspinall, Chairperson of the Hillsborough Family Support Group (can also be seen at the bottom of this page)

Complete short task 4 in workbook (10 minutes)

There are a number of ways that social workers can reduce these barriers. This includes attending Local Resilience Forums and working with other professionals to help them understand the role that social workers can play following a disaster. This can also involve the development of information and resources to inform other professionals and the public about the role of social workers in disasters. Having these resources prepared can not only spread the word prior to disasters, but can be invaluable in the event of a disaster to help spread information about the input that social workers can have. These concepts will be drawn on more in the follow-up task for this module and the follow up task for Module 3.

Contextualising disasters

Return once again to this definition of disasters:

Hazard + Vulnerability + Insufficient Response = Disaster

It is important to remember that the hazard is only one part of what makes up a disaster, be that a storm, terrorism, landslide etc. The disaster is created by the wider context, most notably the vulnerability to that hazard, and the insufficient response when hazard is apparent. Frequently then, social workers are typically not directly responding to the hazard itself, but addressing the vulnerability and making up for the insufficient response.

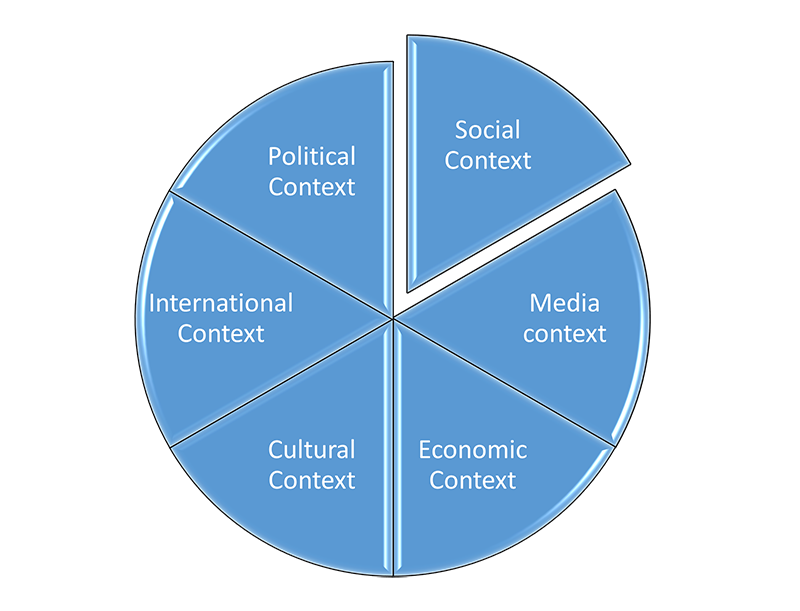

Therefore, social workers must have an understanding of the wider context of what caused a disaster, including the social, political, economic and environmental structures and systems (Pyles, 2017). This will be unique to every disaster, but the list below highlights some of the key areas to be aware of and has examples of questions social workers should be asking themselves and others:

Political context:

What are the likely ramifications for the ruling political leaders? What actions might they take to save face? Whose interests are they likely to protect?

International context:

Are there international organisations/countries involved in the disaster response/recovery? What interests/values do they bring with them? Who is financing them?

Cultural context:

What are the cultural needs of those impacted by the disaster? How likely are these to be met by disaster responses/plans? Who needs to be engaged to highlight these cultural needs?

Economic context:

Where is money for the response/recovery coming from/going to? Who is being impacted the worst financially, and who is being saved from that impact? Where does funding need to go to address those impacted by the disaster?

Media Context:

What views are mainstream media outlets prioritising in their coverage? Whose views are being ignored? How can media (including social media) be used to improve the disaster response/recovery?

Social context:

What has been the impact on marginalised communities? Are they having their voices heard? How can social workers advocate for those impacted? What has been the impact on the local environment that people rely on?

Social workers must also understand their own context. As highlighted in a previous section, the governance of social workers during a disaster situation is devolved to individual local authorities. In the event of a disaster, local authorities are therefore reliant on the “spare” capacity of social workers to respond. This approach has been adopted largely so as not disrupt the everyday commitments of social workers in already stretched local authorities. However, the reality that this “spare” capacity exists has been challenged, most notably due to increasing cost-efficiency and austerity pressures (Dominelli, 2020). This also means that capacity to respond to disasters varies significantly across the country and relies on trained volunteers and local authorities’ willingness to implement necessary secondments (Eyre, 2008).

Watch the video resource of Andy Burnham, Mayor of Greater Manchester (can also be seen at the bottom of this page)

The paragraphs below identify some of the contextual factors that were relevant to the Manchester Arena Bombing that social workers would have needed to account for/understand.

Preparation

There was initial confusion in the health and social care response to the incident, as highlighted in the Kerslake Report. More co-ordinated planning and preparation could have therefore improved the response provided.

Response

Many of those impacted came from different parts of the country to attend the concert, meaning the response had to involve a large number of local authorities. Not all of these would know that someone returning from the concert lived in their area.

Recovery

The bombing was perpetrated by a suicide bomber claiming to support extremist Islamic beliefs, and this led to an increase in Islamophobic political discourse and hate crimes perpetrated against Muslim populations throughout England.

Complete short task 5 in workbook (15 minutes)

Case Study: The Troubles

The troubles refers to the 30 year period of ethno-nationalist sectarian conflict between two populations in Northern Ireland, commonly referred to as nationalist republicans (mainly self-identifying as Irish or Catholic) and unionist Loyalists (mainly self-identifying as British or Protestant). Over 3,600 people died and approximately 40,000 were injured during this period.

The deep rooted historical, socio-political, geographical, economic and cultural context of the troubles make it a unique kind of disaster for the UK. This context shaped social work practice during the troubles, and in the aftermath. The BASW report Voices of Social Work through the Troubles 2019 highlights the experiences of social workers working during this period, and the issues they faced including:

- Less than half of social workers reported receiving support from their employer when they experienced violence:

After one incident, where I was threatened by a group of masked paramilitaries, my line manager instructed me to return to the same house the following day.

- The importance of peer support:

You debriefed with your colleagues when you came back, largely informal peer support.

- The need for creative practice:

Our employer issued any professional who wished an armband indicating that we were essential services so that we could more easily pass through paramilitary roadblocks.

- A lack of training/education in how to manage these issues:

We were in the midst of The Troubles and it was all too painful to deal with in a class of people from different backgrounds

- A culture of ‘getting on with it’ and not addressing the context:

The trauma of living in besieged communities was not spoken about openly in the staff team let alone with the families. It was a known but an unspoken truth with a focus on normalisation.

- Lasting impact/legacy of the experience:

Direct experiences of threat to me were profoundly frightening—as much for the threat they posed to my family and colleagues, as to me. This deeply affected my mood and behaviour at times.

It has made me very resilient, I can manage high levels of stress, I am not afraid of conflict and can mediate well in these situations.

Read and download the full report (can also be seen at the bottom of this page)

Reflection

Is there anything from your own experience or working that you see reflected in any of these quotes?

Disaster capitalism

Disaster informed social workers, taking the time to understand the wider context of a disaster, must be prepared to identify and challenge situations and networks that are potentially exploitative following a disaster. The aftermath of a disaster often involves different stakeholders who have varied, and frequently conflicting, priorities for disaster recovery. For example, government attempts to boost the local economy and invest in new businesses could conflict with social work efforts to build relationships and empower locals to guide their own recovery.

Complete short task 6 in workbook (10 minutes)

A conflict of priorities may not be as inevitable as is often suggested. Dominelli (2013) argues that a sustainable development approach, based on environmental justice, could provide job opportunities for those who lost their livelihoods, whilst also repairing damaged environments and mitigating the potential of future disasters. This needs to involve adequate financial support provided to local residents to support their own recovery, beyond the provision of immediate emergency needs. Social workers can play a central role in advocating for this approach and linking residents with these resources.

However, disasters are also frequently seen as opportunities to gain advantage, both politically and financially. In her 2007 book The Shock Doctrine, social activist Naomi Klein describes in detail how disaster response and recovery frequently prioritises the needs of economic, political and financial systems at the expense of local communities, or what she terms “disaster capitalism”. For example, she explores the response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005 in the USA, suggesting that for private companies no opportunity for profit was left untapped:

When it comes to paying contractors, the sky is the limit; when it comes to financing the basic functions of the state, the coffers are empty (Klein, 2007: 409).

A similar situation has been seen during the Covid-19 pandemic in the UK, with local services frequently struggling, and a number of reports finding social workers struggling to provide basic services (for example). At the same time billions of pounds has been spent on private consultants and firms, most notoriously in the case of the Test and Trace system that as of March 2021 has an allocated budget of £37 billion, and is being implemented by a conglomerate of private firms. Despite this large sum of money, a UK Parliament Accounts Committee report found no clear evidence of its effectiveness of the Test and Trace system, and many argue that the funding should be used to support public services to provide this service instead.

Klein (2007) also discusses the role of governments in disaster capitalism, acting to facilitate disaster capitalism. Similarly, the UK government have been found to have acted unlawfully in a number of areas since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. This includes in their role in allocating contracts to private organisations for the procurement of personal protective equipment (PPE).

More directly relevant to social work, the aforementioned Adoption and Children (Coronavirus) (Amendment) Regulations 2020 (widely known as Statutory Instrument 445) was introduced during the Covid-19 pandemic ostensibly in order to reduce pressures on social services and care providers supporting children through removing a number of core legal protections. However, following a campaign by the charity Article 39 and supported by a large number of organisations and individuals (including hundreds of social workers), the failure of the government to consult widely on the changes was found to have been unlawful. It is noteworthy that while children’s rights organisations and the Children’s Commissioner were not consulted in making these change, private care providers were, once again suggesting a priority towards protecting financial and business interests during disasters.

Social workers should build on the inspirational example of resistance to disaster capitalism that was encompassed in the challenge to Statutory Instrument 445, and challenge recovery approaches that prioritise the needs of politicians and financial organisations over local communities and marginalised communities. At times this needs to include involvement in activism and stepping outside of their (often statutory) remits. Each social worker should reflect on their values, and the specific contexts of a disaster, in order to determine any action they should take. These points will be discussed in more detail, with a focus on social work ethics, in Module 4.

Follow up task

Based on your learning from module 1 and 2, design a flyer that outlines the role of the social worker in a way that could be understood by other professionals and members of the public with ease. This should be designed to be used both before and during a disaster to spread this awareness. It may be advisable to return to Section 2 of Module 1 that gives a broad overview of the role of social workers in disasters. But remember, it needs to be accessible to those unfamiliar with social work jargon.

Following the development of this flyer, discuss with your manager/supervisor/colleagues about how it could be distributed.

Write a brief reflection on your experience of undertaking this follow up task: (complete in workbook)

References and Further Reading

Cabinet Office (2013) Preparation and planning for emergencies: responsibilities of responder agencies and others, London: TSO.

Dominelli, L. (2013) ‘Mind the gap: Built infrastructures, sustainable caring relations, and resilient communities in extreme weather events’, Australian Social Work, 66(2), pp.204-217.

Dominelli, L. (2020) ‘A green social work perspective on social work in the times of Covid-19’, International Journal of Social Welfare, Early Access.

Duffy, J., Campbell, J., Tosone, C. (2019) The Voices of Social Work through the Troubles. Birmingham: British Association of Social Work.

Eyre, A. (2008) ‘Meeting the needs of people in emergencies: a review of UK experiences and capability’, Emerging health threats journal, 1(1), DOI:

Klein, N. (2007) The Shock Doctrine, New York: Penguin.

Pyles, L. (2017) ‘Decolonising disaster social work: environmental justice and community participation’, British journal of social work, 47(3), pp.630-647.

Video resource: Margaret Aspinall, Chairperson of the Hillsborough Family Support Group

This clip is part of Module 2: Skills for disaster working

Video resource: Andy Burnham, Mayor of Greater Manchester

This clip is part of Module 2: Contextualising disasters

Voices of Social Work Through The Troubles

Download the full report referenced in section contextualising disasters as part of a case study.