Preparation (1 hour)

Read Banks et al. (2020) ‘Practicing ethically during Covid-19: Social work challenges and responses’, International Social Work, Online access.

Learning goals

Following this Module you should be able to:

- Develop creative and ethical responses to the unique/unpredictable challenges.

- Apply relevant social work theories and models for disaster response.

- Practice self-care and utilise available support.

Full details on the learning goals on which this, and other modules in this series, are based, can be found via the Social Work in Disasters overview page. You can also find an assistive glossary on this page we recommend you refer to.

Consider while reading:

- If you were working during the Covid-19 pandemic, how do these experiences resemble your experience?

- What can be learned from the experiences of social workers internationally in responding to these challenges?

- Thinking about what you have learned through this training up to now, how would you respond to the ethical dilemmas posed in the article?

Module 4

Utilising social work theory

Social work theory has been discussed throughout this training and as a social worker you have your own knowledge in this area. Therefore, this section should be considered as merely a brief overview of some of the theories that have been identified for working in disasters for social workers to get you thinking about them and applying them to the specific context of disaster working. You are encouraged to review and revise relevant theories in more detail, and with a focus on your specific professional context and experience.

Complete short task 1 in workbook (10 minutes)

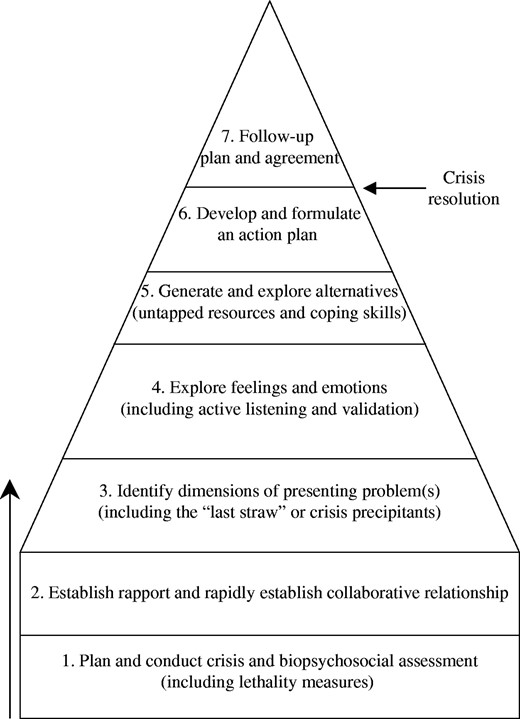

One of the theories highlighted regularly in research around disaster working is crisis intervention. While there is a wealth of literature on the topic of crisis intervention working, the following seven stage approach drawn from the work of Roberts and Otten (2005) is particularly pertinent to social work and can be implemented in most contexts when facing a crisis, including disasters:

This model starts at stage one, and moving up through the seven stages towards resolution and review (although there is some scope for moving up and down the stages). Taking the example of a fire, for example, this model could be utilised to support someone in the immediate aftermath, starting with immediate assessment of danger (ongoing risk to life or limb), and then building rapport to work with the individual or family around their ongoing problems, feelings and emotions until an action plan can be developed.

Complete short task 2 in workbook (15 minutes)

Find out more about the Roberts and Otten model

This should be read before trying to implement the model if you are unfamiliar with it.

Another important theory that social workers could draw on in these contexts is trauma informed working. Social workers, whether working in disaster contexts or in their day to day practice, frequently encounter people with a history of trauma, and so you likely have some experience in this area already, even if you do not explicitly utilise trauma informed approaches.

Trauma informed social work practice recognises the impact that trauma can have on people’s lives, and how many actions or behaviours that are characterised as problematic could otherwise be characterised as coping strategies for managing trauma. Social workers working from a trauma informed perspective highlight the importance of safety, trust, collaboration, choice and empowerment, as well as being constantly aware of not inadvertently exacerbating the trauma the individual is dealing with. Following a disaster this point becomes particularly important, because often the government has been in some way culpable for the disaster that has unfolded, and social workers are often working for that same government.

In the case of the Grenfell Tower Fire 2017, social workers working for Kensington and Chelsea local authority reported the difficulty they had in forging relationships due to their association with the council that many saw as to blame for the fire and ignoring the concerns of residents. Similarly social workers supporting people impacted by the Hillsborough Stadium disaster have described that the support they offered was not always well received, with social workers being perceived as representing the state. Research has found that many state-led initiatives that followed the Hillsborough disaster exacerbated the impact on those they were seeking to support (Coleman et al., 1990; Scraton, 1999).

Levenson (2017) suggests that trauma informed social work can be integrated into other models and workplaces, and her article on trauma-informed Social Work Practice should be read for more details on this approach.

Complete short task 3 in workbook (15 minutes)

Other theories that are highlighted as important for disaster informed social workers have been discussed in previous modules, including rights based working (Module 2), strengths based working (Module 3) and anti-oppressive practice (Module 2). If you are not confident in any of these areas, you are encouraged to revisit those sections, and take some time to explore these theories more.

Creative responses

The following quote comes from the Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report on the Grenfell Tower Fire that was discussed in more detail in Module 1.

It was chaos. There was no-one doing anything, there was no-one taking control, there was no council, there was no police, there was no-one. It was just volunteers, it was just the community. So, it just opened and then everyone had to just organise themselves. Where’s the food going to go? Where’s the drinks going to go? Where’s the nappies going to go? Where’s the creams going to go? There was no liaising with anybody whatsoever. It was just manic. And then people started bringing beds, so then someone made the decision, like, “right, we’re going to make the tennis courts into bedrooms” so they can sleep there that evening...I think they [the council] turned up at about seven o’clock in the evening, the next day (Grenfell Community Stakeholder)

That report outlines a number of ways that services struggled to be flexible following the Grenfell Tower fire, and the good practice that was seen when flexibility was employed and practitioners felt able to use their professional judgement.

Similarly social workers responding to disasters need to be confident to step outside the usual parameters of daily practice and respond to the specific challenges of posed by the disaster. This is captured in a number of the quotes from social workers working during the Covid-19 pandemic that were captured in the preparation reading for this module (Banks et al., 2020). For example:

I am seeing the task of carrying on delivering social work during this period as a kind of intriguing puzzle that loads of very creative and determined people are trying to solve. (Independent social worker, UK)

Some looked after children are highly stressed by the Covid-19 outbreak and being creative and flexible around supporting them is very important in my view. (Social worker, UK)

However, it is also recognised that social work roles in the UK, and in particular England, are narrowing, and becoming more focused on statutory tasks such as needs assessment and safeguarding, at the expense of community development and early help (see for example, Tunstill (2019)). This is linked to reduced funding for services, and the fact that children and family services have been decimated by government austerity policies in the past ten years in particular. This context is important in shaping how social workers respond to disasters, because it means that the resources required are not always available. The narrowing of the social work role also contributes to a culture whereby social workers are less confident in responding to situations and contexts that fall outside this statutory context. Read, for example, the following experience of a social worker working in England:

We received an email stating that there had been a gas explosion and multiple casualties not far from the council building, and were asked if anyone had the time to go down and support those impacted. Being in an open-plan office, this led to widespread staff discussions about what support we could provide, including mention of eligibility criteria, and ultimately few felt confident to go down there and support. In hindsight, this was a shocking indictment of what social work has become, and it is really worrying that few could think about the importance of just being there and supporting these people going through a crisis using the social work values and skills we all possessed. Ultimately a newly qualified social worker was the first to volunteer and was sent to the scene, probably because he had been less indoctrinated into our statutory focus and context (Social Worker).

Unfortunately, the contextually specific nature of most disasters makes it difficult to provide precise guidance on how to be creative in the response provided, while also making it vital that this creativity is employed. This training has made reference to tools, techniques and approaches that can help to support following a disaster, but your own professional judgement will be most significant in determining what approach to take in all cases. Thankfully, this is not so different from what social workers should be doing regularly, it just takes the confidence to step outside your usual role.

Some examples of creative responses to disasters that social workers and other professionals have shared include:

- Arranging mental-health community workshops following the London Bridge and Borough Market terrorist attack 2017.

- The use of the WhatsApp messaging application to coordinate social work interventions following flooding of council building in Rochdale 2015.

- Using improvised stretchers made from crowd control barriers to remove injured people following the Manchester Arena terrorist attack 2017.

- Social workers using poetry to support survivors of the Grenfell Tower Fire 2017 to express their feelings and share their experiences.

Complete short task 4 in workbook (20 minutes)

It is important that the need for these creative responses does not negate the importance of social workers being involved in disaster planning and preparation, both within their own context and alongside other professionals. To paraphrase Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham speaking at a December 2019 conference on the role of social work in disasters about his experience following the Manchester Arena Bombing in 2017: “you will never strictly stick to a plan, but having those plans makes the flexibility required following a disaster much more effective”.

Ethical responses

With the added creativity and flexibility that is usually required in working in disaster contexts, it becomes all the more important that social workers underpin all of their work with the core ethics of the profession. This links to the discussion above about trauma informed practice, whereby you need to be aware of the potential for your actions and practice to exacerbate trauma. These points also link to the learning in Module 1 around culturally appropriate support, and Module 2 around disaster capitalism and the need to challenge organisations and individuals that seek advantage from disaster situations. You are encouraged to revisit these sections and link this learning to this section.

Thankfully though, ethical awareness is recognised as fundamental to the profession of social work. The British Association of Social Workers Code of Ethics can be taken as a starting point for revising your knowledge around social work ethics, and thinking about their application to disaster working. The code of ethics outlines the values and ethical principles that social workers should be adhering to in all their practice, including when working in disaster contexts. The principles encompass many areas that have already been explored in this training, such as human rights, social justice, and challenging networks of exploitation.

Complete short task 5 in workbook (20 minutes)

In order to practice ethically, social workers must take the time to listen to and understand the experiences of those impacted by disasters. This may even include challenging or disregarding employer or government guidance at times when professional judgement and ethics demand it, similar to the requirement to step outside of statutory remits that was outlined above. Consider the following quotes from social workers captured in the preparation reading for this module (Banks, 2020):

We are running into many cases of depression, anxiety and homeless people, without medical plans and without family members. Worse still, on many occasions we have contacted many government agencies to seek help for our service users and we have no response. (Social worker, Puerto Rico)

I understand my country’s system is not as efficient compared to others, it has a lack of resources unlike other countries. But the system we have needs to step up further with or without Covid. As a social worker, it is not a work of one, it needs togetherness and cooperation from different agencies to help with the decision making. (Social worker, Brunei)

To what extent am I allowed to trust my common sense and professional senses and not follow these guidelines? (Social worker, The Netherlands)

In the circumstances outlined in these quotes, if the social workers involved waited for official government guidance before acting, or strictly follow the government guidance that does exist, then they may not be meeting their requirements as ethically practicing social workers.

There is a particularly resounding example of this stemming from the Covid-19 pandemic, related to the discharge of patients to care homes. In hindsight we know now that discharging patients to care homes who were Covid-19 positive during the first wave of the pandemic caused untold deaths within care homes, not just in the UK but in many places throughout the world. These patients were discharged in line with government guidance, most notably the rapid discharge of patients through the Discharge to Assess pathway. It is now worthwhile to reflect on the ethics around the decisions that were made at that time, as well as if/how they could have been challenged, including by social workers.

There are other examples from previous disasters where social workers adopting an ethically appropriate challenging stance could have prevented some of the impacts of a disaster. Following the Grenfell Tower Fire 2017, it was found that the lack of evacuation procedures for disabled residents was down to strict following of government guidance in this area that relied on emergency services helping these residents to exit the building. Therefore, it is worthwhile once again to reflect on how an ethically focused challenge to this approach could have been utilised to alter this approach, and what role social workers could have played in this.

Complete short task 6 in workbook (15 minutes)

Taking the time to listen to those impacted by disasters, hear about their experiences and understanding the communities they live in, will be central to determining the ethically appropriate response that you engage in. As in most aspects of this training, you are expected to integrate you knowledge, skills and experience of working as a social worker to assess the circumstances you are faced with.

Organisational support

Before discussing the importance of self-care when working in disasters, it is vital to highlight that social workers should not be expected to take full responsibility for their mental and physical health and wellbeing, either in their day to day practice, or when responding to disasters. Employers have obligations under the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 and the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999 to ensure, as far as reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare of all their employees. This includes the risk of stress.

Unfortunately, social work employers do not always have the greatest track record in supporting the wellbeing of social workers, and social workers consistently rank their working conditions as some of the worst in the country (Ravalier, 2017; Ravalier et al.,, 2020). This is worrying in day-to-day practice, but also brings with it significant risks when social workers are asked to step outside their usual remit, including in responding to disasters, which bring additional stress and strain to practitioners. Therefore, when volunteering or being asked to respond to a disaster, it may be important first and foremost to ask your employer what support they will provide you with, including:

Relief from you usual workload

You should not be required to both manage your usual caseload and also respond to the specific challenges of a disaster.

Debriefing session, daily if necessary

These are different to supervision, and are designed to allow you to process the events that you have been involved in and the experiences you have had. They can be collective or group focused, or just you and a supportive manager or colleague. However, it is important that these are not required/imposed on social workers who do not find them helpful, otherwise they can be perceived as punitive.

Support to stick to your usual working hours

Some disaster work will go on for extended periods of time, and therefore it is important that you are able to maintain separation between your personal and professional working. This includes continuing to take weekends, annual leave and sick days.

Information about your remit/role

While working in disaster contexts requires creative and ethical responses, it is also important that, insofar as possible, you are provided with clear information about your remit and role in responding. Your employer and you should both be on the same page about this.

Access to easily accessible counselling support

This should not require going through your manager to access, and should be 100% confidential. Social workers should hopefully always have access to this type of support, but it becomes particularly important due to the challenging issues that social workers face in working in disasters.

Peer support/buddy systems

While some social workers will feel confident and capable to discuss their experiences of working in disasters with colleagues, others may feel less able to. Therefore, a buddy system of peer support can help to ensure everyone has someone to go to. It can be helpful if this involves linking a social worker who is actively working in the disaster situation with someone who is not, and therefore has the level of distance required to provide support.

Reflection time

As well as debriefing time, social workers working in disaster contexts should be provided with reflection time to examine their own feelings around the work they are doing, and to consider many of the factors raised in this training, such as the application of theory, the need for ethical decision making and how to prioritise the views of those impacted.

Respect for your professional judgement

Working in disasters often requires you to step outside your usually working role, and to be confident to apply creative and ethical responses to the challenges faced. Without the respect, and backing of your employer for your professional judgement to be used in these contexts, you are liable to feel persistently stressed about whether you are making the right decision, which will negatively impact on your ability to help those who need it.

Complete short task 7 in workbook (15 minutes)

Ultimately, employers should avoid a culture of “just getting on with it” during incidents which are anything but normal. Social Care Institute for Excellence research suggests that one of the most harmful approaches that organisations can adopt when their employees are working during disasters is a “business as usual” approach, which can delay the ability of an organisation to recover from the experience. You may also remember the BASW report on the Troubles in Northern Ireland that was discussed in Module 2, some of the social workers in that report described the harmful impact of a culture of “just getting on with it” and the long term impact that it had on them. You are now encourage to revisit that report with this new perspective.

As a disaster-informed social worker, you should feel confident to challenge your employer to provide you with the support you require in these contexts. This can be difficult, but in particular for local authority social workers, it is important to remember that your employer not only has a responsibility to respond to disasters under the Civil Contingencies Act 2004, but also has these legal responsibilities around your welfare. Looking at these legal obligations collectively should provide you with an effective foundation for challenging your employer to provide you with the adequate support required to undertake working in disaster contexts.

Self-care

Watch this short video about self-care in social work: Self-care for Social Workers

It is not unplanned that this training finishes on the topic of self-care. The topics and issues discussed throughout the four modules you have worked through have not always been easy, and you have been challenged to question your own practice, your own position and how you could/would respond to some of the most complex circumstances that social workers come across. There are a number of strategies that have been highlighted by social workers who have experience of working in disasters that have supported them through the experience, including:

- Checking in on yourself – taking the time, at least once a day, to ask yourself how you are doing, and if you are not doing well, trying to identify why that is

- Make use of employer support – the previous section raised the importance of challenging your employer to provide you with sufficient support. However, you also have a responsibility to make use of this support

- Maintain your personal routine – this includes hobbies, engaging with friends and sleeping

- Use tools and techniques that work for you – consider, for example, exercising, mindfulness, the use of humour or writing reflective records

It can be difficult to engage in self-care or come up with ideas for self-care when working in disaster contexts. Therefore, you are encouraged to develop a self-care plan and to have this ready to draw on if you are ever working in disasters (or really if you are experiencing any sort of difficult or challenging time in your social work role). This can include information about your support network that you can draw on for support (colleagues, friends, family), strategies for managing the difficult circumstances (hobbies, meditation, reflection), information about support you will require from your employer (caseload relief, allocated buddy support, debriefing sessions) or anything else specific to you that you think will support you in these contexts.

Complete short task 8 in workbook (25 minutes)

Follow up task

In line with the theme of self-care, your follow-up task for Module 4 is to take at least an hour and do something for yourself. This does not include working on your caseload! This training has been challenging and dealing with some very heavy topics, it is important that you are comfortable and able to now step away from it, and turn your mind to something else.

References and Further Reading

Banks, S., Cai, T., de Jong, E., Shears, J., Shum, M., Sobocan, A., Storm, K., Truell, R., Uriz, M. and Weinberg, M. (2020) ‘Practicing ethically during Covid-19: Social work challenges and responses’, International Social Work, Online access.

Coleman, S., Jemphrey, A., Scraton, P. and Skidmore, P. (1990) Hillsborough and After: The Liverpool Experience First Report. Liverpool, Liverpool City Council.

Levenson, J. (2017) ‘Trauma-informed social work practice’, Social Work, 62(2), 105-113.

Ravalier, J. (2017) UK Social Workers: Working Conditions and Wellbeing, Bath: Bath Spa University.

Ravalier, J., Wainwright, E., Clabburn, O. and Smyth, N. (2020) ‘Working conditions and wellbeing in UK social workers’, Journal of Social Work, Early Access.

Roberts, A. and Ottens, A. (2005) ‘The seven-stage crisis intervention model: A road map to goal attainment, problem solving and crisis resolution’, Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 5(4), 329-339.

Scraton, P. (1999) Hillsborough the Truth, Edinburgh: Mainstream.

Tunstill, J. (2019) ‘Pruned, policed and privatised: The knowledge base for children and families social work in England and Wales in 2019’, Social Work and Social Sciences Review, 18(1), 57-76.

Congratulations! You have completed the online training.