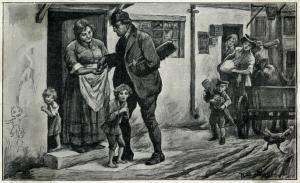

Children have been forsaken throughout history

Published by Professional Social Work magazine, 9 December, 2021

[This is a revised version of an article that first appeared in the July/August 2021 edition of PSW magazine]

The national inquiry into the killing of Arthur Labinjo-Hughes is a typical knee-jerk reaction from politicians when ghastly events like this happen. Make no mistake - it will be a scapegoating exercise just like the dozens I have watched in the course of my child protection career.

Yet official data tell us that one child is killed on average every week in the UK by parents or carers, and according to UNICEF, 95,000 every year. Where is the public and media outrage over those numbers?

The recent damning report into the state of children’s services is the latest in a long line of evidence, and a clear warning about children’s safety. Proof that children aren’t a priority for politicians.

Recent police data shows in 2020 there were 22,251 recorded offences against children, an increase of 3,000 from 2019 compared to 6, 611 recorded in 2010. During the first half of 2020 there was an increase of 27 per cent in serious incident notifications, 119 children died as a result of child abuse and 153 seriously harmed.

Child murders receive the highest media profile especially where public services are involved in attempting to protect a child at risk of harm. We all remember the horrors of Baby Peter in 2007.

The pattern over the past 50 years is a familiar one. A child murder receives blanket news coverage, official investigations are undertaken, politicians seek to blame and scapegoat, rapid ill-thought through changes to legislation or professional guidance ensues.

Social workers and others responsible for safeguarding vulnerable children have systems disrupted, procedures changed and government directives shift the emphasis of work with families to a more inspectorial rather than preventive mode. In Economic times of hard choices the more initially expensive options of family, psychological, and financial support are abandoned.

This lack of safeguarding and preventative measures has a direct impact as the prevalence of child deaths and child abuse in general inexorably rise, especially at times of financial hardship and unemployment.

The link between child abuse and poverty is contested by politicians, despite high quality research going back many decades indicating poverty as a risk factor in child abuse. There are currently four million children living in poverty according to government figures. You can add parental mental illness, poor housing conditions, unemployment, drug and alcohol misuse as risk factors.

From ancient times to Maria Colwell

Yet there is another more disturbing thesis about why child abuse endures and is so resilient to government intervention. It is that child abuse has been hidden, excused, denied or covered up, and has been since the beginning of recorded history.

There is a wealth of compelling evidence showing infanticide, incest, child sacrifice, predatory child sexual abuse and physical child abuse was normalised and part and parcel of ancient life. Even as civilization evolved, children lived short and brutal lives.

Throughout the Middle Ages where childhood as a concept didn’t exist, children worked as soon as they were strong enough and the 18th century industrial revolution meant that children could be used as cheap labour in dangerous mills, mines and factories.

19th century Victorian Britain was rife with young girls forced to sell sex to stave off poverty, and then blamed for spreading venereal disease among their wealthy ‘clients’. In America, in the late 19th century, legislation to protect children only passed because it was tacked onto laws to protect animals from abuse.

Attempts to seriously protect children didn’t happen until the beginning of the 20th century in Britain but there was resistance to the idea of interfering in family life and the rights of parents to do what they wanted with their offspring.

The death of Dennis O'Neill, who was killed at the age of 12 by his foster father in 1945, started to change the public’s perceptions. This shocking event prompted the first formal child death inquiry in England which produced the Curtis Committee Report recommending changes to child welfare services.

The work of a series of pioneering Paediatric radiologists also helped drive concerns about child protection in Britain and America. Doctors in the mid 20th century conducted research which utilised x-ray data to understand and to make visible the injuries of physically abused children for the first time.

It was paediatrician Henry Kempe who coined the term Battered Child Syndrome in an American professional journal in 1962 that captured International headlines. It was the first concrete evidence of routine child abuse within the family and alerted generations of doctors to the problem.

In 1973 the death of seven-year-old Maria Colwell led to the establishment of Britain’s modern child protection system. Further changes evolved after inquiries into several other child deaths, including four-year-old Jasmine Beckford in 1984.

'There aren't many votes in children's services'

Yet in 21st century Britain the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse and police research has exposed the scale of child abuse within state and religious establishments, online predatory paedophile activity, and everyday sexual harassment of schoolgirls.

It’s astonishing to think that it was only in 1989 that the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of the Child was endorsed by most member nations, 6,000 years after the first evidence of child abuse was recorded.

In the same year The Children’s Act 1989 codified and strengthened existing law and regulations to better protect children from harm, 100 years after the first UK legislation offering limited protection.

The history of childhood is the history of child abuse, it has never stopped and there is still considerable denial about the scale of abuse and the impact it has on adult survivors.

Child abuse runs through the fabric of our society still and predominantly occurs within families. It respects no class, wealth, gender, educational, cultural, ethnic or religious differences.

The government’s review of children’s social care in England is to be welcomed. Hopefully this latest review will match the expectations of professionals and parents concerned about the poor state of children’s social care and the repeated failures of the existing system.

But there aren’t many votes in children’s services as cynical politicians will admit. As this new decade begins much work remains to be done to protect all children, and to do that society needs to acknowledge how children have been truly forsaken since time began.

Steven Walker is visiting lecturer in social work at Essex University. His book Children Forsaken: Child Abuse from Ancient to Modern Times is available at www.criticalpublishing.com/children-forsaken