Despite social distancing, we must not lose focus on co-production

Professional Social Work magazine - 8 September, 2020

In the face of the Covid-19 pandemic many public services quite rightly halted co-production activities. As it becomes clearer remote working is here to stay for the foreseeable future, it’s imperative that we find new ways to facilitate co-production in safe and supportive ways.

Co-production as a concept has been discussed since the 1970s, forming part of the ‘neighbourhood movement’ in the 1960s and 1970s in the USA. In 1980, political scientist Gordon Whitaker described the relationship between professionals and residents participating in service delivery as “agent and citizen together produce the desired transformation.”

The TLAP (Think Local, Act Personal) National Advisory Group defines co-production as “an equal relationship between people who use services and the people responsible for services.” whilst the Care Act 2014 statutory guidance states that “ ‘Co-production’ is when an individual influences the support and services received, or when groups of people get together to influence the way that services are designed, commissioned and delivered.”

Co-production then, is a process that practitioners facilitate in order to encourage and support service users, residents and interested stakeholders to get involved in designing, commissioning and supporting service evolution by providing meaningful participation opportunities.

There is no one model of co-production, it is bespoke to each project. Co-production can be undertaken as creatively as practicable. From experience, co-production is enjoyable, people are willing to engage and where pathways or procedures become more technical, a modest amount of training is all that is required to enable meaningful involvement.

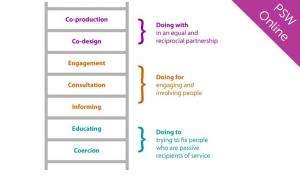

The TLAP Ladder of Co-production below shows seven ways of working with people. These range from ‘coercion’ and ‘educating’ - which just involves telling people what you’re doing - to ‘informing’, ‘consultation’ and ‘engagement’, which creates more of an environment of working with people to seek their feedback.

This does not necessarily mean that you use that information to ‘co-design’ and for ‘co-production’, which involves an equal relationship between people and facilitators.

The benefits of co-production include being person centred, increasing the likelihood of projects succeeding; it’s grass roots and community owned; it ensures services meet the needs of local communities; it moves away from council managed services to community involvement – the concept of done with rather than done to.

It also encourages innovation within the community; gives value to what we are doing; provides value for money in the long term; can promote wellbeing; creates links with the community; can improve public perception of the local authority and is a requirement in the Care Act 2014 and Local Government Act 1999.

Recent research by the Social Care Institute for Excellence shows that 94 per cent of carers and people who use services believe commissioners and service designers should utilise co-production more in social care.

The vast majority of people who use services and carers (95 per cent) said they would prefer to use co-produced services, and 96 per cent of people employed in the social care sector say they would prefer to work in services that were co-produced.

Co-production myths

So, with all these advantages of co-production, why is everyone not doing it? Here are some of the commonly perceived disadvantages of co-production that we have heard and how you can mitigate against them.

Myth one: Co-production is expensive. The highest cost incurred through co-production as a commissioner has been the design cost of the carers’ strategy document, everything else is either low cost such as refreshments or free, such as room hire and people’s attendance.

People want to get involved in these types of activities if they are given the opportunity, so they are happy to attend an event to volunteer their time. This is especially true for virtual workshops which would carry no cost of room hire or refreshments.

Myth two: Co-production is time consuming. Probably one of the most common myths. Co-production needs to be factored into your project lifecycle. At the beginning of a project work can be done with a community in order to better understand their needs. Then over the course of the project, workshops can be held which require varying levels of input from people.

For example, when designing a service specification for a carers’ service, we held successive focus groups with different groups of carers were held over a period of one month. The workshops started with a blank sheet, plotting the client journey. Then as the workshops progressed, so did the service specification, until a finished product was taken to the Carers Partnership Board for final comments. This took no longer than it would have done without the workshops.

Myth three: Co-production creates difficulties in managing expectation. This requires the facilitator to the ensure scope is defined in order to manage expectations of the event. People are aware of the finite resources available to the public sector so are likely to provide you with reasonable solutions and help you to explore feasibility of project.

Workshops should be open and honest, facilitators should set the scene, let people know what can and cannot be achieved and what the constraints are. People are more than willing to understand if they feel they receive a suitable, logical explanation. Frustration from the public only occurs when they feel they are not being listened to.

Myth four: Co-production results in people feeling that they are repeating themselves. A side effect of what we term none-meaningful engagement. To alleviate this, you only need to ensure people are aware that any previous feedback they have given has been acknowledged and used. This can be done by setting the scene at the beginning of an event and by feeding back to people after the event, by bulletins or returning to groups to update on progress.

Myth five: Co-production is just a platform for people to complain. Of course, there will be people you meet who are unhappy with services and they have a right to say. To some extend facilitators can listen and empathise, however where the subject is clearly going off track, it is your role as a facilitator to bring the subject back. This can be done by setting the scope of the event, define the project and when necessary, bring the subject back inline by politely encouraging people to take a complaint via a certain route.

From my experience as a carer and chair of a service user involvement group, co-production is a game-changer. We can feel pretty useless if we are 'done to’. Co-production gives us agency. We feel respected, useful and valued. We learn to understand the challenges you face every day and want to work with you to do the best we can within available resources. Better results, better value, true creativity and mutual respect and understanding can all come from co-production.

Co-production post lockdown

As lockdown is relaxed, services in local authority will begin to return to business as usual. Commissioning cycles will need to engage with the community in order to ensure their views and needs are identified and utilised.

We cannot use Covid-19 as a reason to turn to bad practice. Here are some helpful ideas that can be used to facilitate co-production in a safe way using an online platform to create a virtual workshop:

- all participants must be muted to reduce interference

- use the chat or raise hand function for people who would like to speak

- their video does not need to be on

- you can share screen to provide a presentation

- groups can breakout by a facilitator initiating separate calls or using different channels to smaller groups

The obvious criticism here is that this disadvantages people who are not computer literate. Whilst that is true to some extent, lockdown is likely to have significantly reduced this number and we as practitioners can only do what is reasonably expected of us within our given environment. Furthermore, I think sometimes we undersell just how able the people in our populations are. Think of it as an opportunity to increase computer literacy in addition to a co-production event.

In mid-March I undertook a workshop with colleagues to develop a theory of change model for a new service. Ten of us were on the workshop. We broke out into two groups by creating separate calls, then re-joined the main workshop at a set time to feedback. It is a strange feeling at first to talk to colleagues and for them not to respond (because they are on mute), but once you are comfortable with this, the workshop will flow well.

Stephen Bahooshy is strategic programme manager for children and adults Services at Southwark Council and Nicky Selwyn is a parent carer and chair of the service user group in Croydon

This article is published by Professional Social work magazine which provides a platform for a range of perspectives across the social work sector. It does not necessarily reflect the views of the British Association of Social Workers.