PSW: How it all began

‘As the years pass I realise increasingly how many things there are that I cannot do, persons I cannot help... But there are a few things I can do. I can take off my hat to... Lady Almoners... when I see a beautiful piece of work. The almoner is an artist in human relations. We must learn from you here’ – American physician Richard Cabot on the work of the St Thomas’s Hospital almoners, 1918

Ever since I discovered that my father grew up in care, I’ve been fascinated by the idea of society looking after its most vulnerable citizens.

I registered as a foster carer as soon as my birth children were old enough and became an adopter a few years after that. But it was when I began researching my father’s family history a few years ago that I came to know more about the origins of the modern day social worker.

For centuries, the Church, Salvation Army and social reformers worked hard to feed and shelter the sick and the poor. It was in 1885 that the General Secretary of the Charity Organisation Society (COS) first recognised the need for a “charitable co-operator” in a hospital setting.

“What more glaring picture of charitable impotence is there,” Sir Charles Loch commented in 1892, “than that destitute persons should constantly apply to a free dispensary for drugs which cannot benefit them if they lack the necessary food?” Loch envisioned the co-ordinator complimenting the work of physicians “by obtaining the general assistance without which medical relief will often fail in its purpose”.

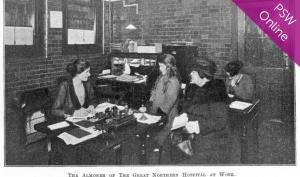

A decade later, on a winter’s morning in 1895, the first almoner, Mary Stewart, turned up for duty at the Royal Free Hospital in London and the profession of social work was born. A reserved and gentle character who carried out her role from a screened-off, airless and dingy corner of the out-patients department, Stewart could not possibly have dreamed that in examining patients through the lens of the environment from which they came, she was setting the foundation for a social movement that would one day become the envy of the world.

Initially, her duties were limited to preventing the abuse of the voluntary hospital by interviewing patients, who would perch themselves on a radiator beside her desk. She would redirect those with the means to pay for their own treatment towards general practitioners, and encourage those who could afford to, to join a Provident Dispensary. She also used her knowledge as a social worker with the COS to refer those in need of charitable relief to the Poor Law Authorities.

Since making an accurate assessment of a patient’s financial position required a home visit, Miss Stewart and her successors found themselves drawn into a wide array of complex social problems, ones that will resonate strongly with social workers today. The toxic trio of alcohol and drug addiction, domestic violence and mental illness, for example, alongside homelessness, incarceration, and, inevitably, the neglect and the deliberate abuse of children.

From the moment I retrieved the Royal Free Hospital’s almoner’s reports from the bottom of a dusty old box in the reading room of the archive, I was struck not only by the hardship experienced by ordinary people, and their utter relief at finding someone sympathetic to their struggles, but also the dedication and compassion of the almoners who tried to help them. It became clear that their role very quickly evolved from assessing a patient’s means, to assessing their needs.

Drawn from a social class superior to those they were employed to serve, since it was felt that only those blessed with eloquence could advocate for society’s neediest, these women might have closed their eyes to the struggles going on around them and enjoyed a refined, easy life at home. Instead they chose to roll up their sleeves and get stuck into the best and worst that working with London’s poor had to offer. A few men were employed early on as almoners, (often retired policemen who could put their investigative experience to use by rooting out cases of fraud) but apparently, they couldn’t cope with the work!

There were the prostitutes suffering with dual infections of syphilis and gonorrhoea who had to be tracked down to ensure that they completed their treatment in the VD clinic; the young women who had been in service but had fallen prey to the attentions of their masters and, after being dismissed from their post, needed help to find somewhere for themselves and their infants to stay. Local families often came to trust the almoners and a dizzying array of domestic horrors were confided over cups of hot sweet tea.

Most challenging of all were the cases where evidence was unearthed that children were being mistreated or abused, so that the almoner, a trusted figure, had to compile evidence against the parents and remove their offspring to safety. Even at the turn of the 20th Century, however, the almoners recognised the benefits of supporting families if at all possible, so that, except in the direst of circumstances, children remained at home.

There were times, either through destitution or ill health, an infant had to be separated from its birth mother. “Sometimes the almoner is called on to... find a suitable home into which young children can be temporarily admitted or find a foster mother for the baby either herself or through an outside agency, and probably raise the funds to pay for this,” according to The Hospital Almoner; A Brief Study of Hospital Social Science in Great Britain, 1910.

“Her aim, in addition to arranging that the children shall be satisfactorily looked after, is to secure as far as possible mental peace for the patient, for worry is a bad bedfellow.”

In the 1920s, it wasn’t unusual for adoptions to be arranged by hospital almoners, matrons or doctors. They identified what they considered to be a suitable match for the child, and the new parents took them home ‘on approval’ with no involvement from local authorities.

As the years passed, the almoner’s role expanded. During the Second World War, they were the ones who ensured that the windows of the hospital were blackened and that hospital entrances were protected with sandbags. They guided patients to safety at the sound of air raid warnings and comforted children down in the bunkers, as bombs flew overhead.

To cope with the demands of such an emotionally draining job, almoners needed special qualities. Dr Fairlie Clarke, a surgeon at Charing Cross Hospital and secretary of a medical charities committee, prescribed that almoners should be of “some education and refinement, of a kind and forbearing disposition, but at the same time possessed of firmness and discrimination of character and tact”.

As any social worker knows, these qualities, along with a sense of humour and a heavy dose of humility, are just as essential today as they were a century ago.

Petrina Banfield’s book about the work of the hospital almoners Letters from Alice is published by HarperCollins