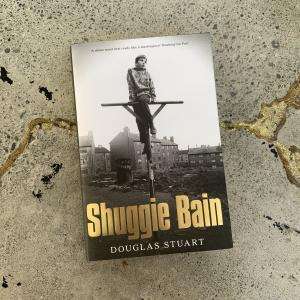

Shuggie Bain – A novel for social work

Published by Professional Social Work magazine - 8 February, 2021

Shuggie Bain is the first novel of Glasgow raised writer, Douglas Stuart. The book opens the curtain on the world after the social worker has gone home.

It chronicles the life of Shuggie, his mother Agnes and to a lesser extent his siblings Catherine and Leek in 1980s and early 1990s Glasgow. Life in an era of industrial decline, poverty and poor housing is the backdrop to the dramas of family relationships, trauma and addiction.

As Stuart writes of the story’s local shop keeper: “The racks of larger cans and whisky bottles behind him said he well understood the new economy of the scheme.”

The story focuses foremost on Agnes, her trauma, Titanic clashes of adult relationships, her struggles as a parent and her alcoholism. Meanwhile her children struggle to make sense of the world around them, find their place and ultimately to survive.

The book has multiple lessons for survival in adversity and accordingly it should be compulsory reading for any social worker.

The vivid depiction of lives lived sits in stark contrast to the often one dimensional and reductive depictions of life in social work reports. There are lessons and reflections for social workers on nearly every page.

Social work is both science and craft when comes to understanding how people live in severe adversity. Here in Shuggie Bain is the craft which, however fictionalised, gets to the point of what is really happening for families.

The language of the West of Scotland working class can be curt and brutal. It is also often vivid, concise and to the point. Things many social work assessments could benefit from.

When Angela’s relationship with Shug, Shuggie’s father, is falling apart and he plans to move the family to a dying pit village, her mother sums up the situation accordingly: “He’s going to take you out there to the middle of nowhere and finish you for good.”

Once she arrived in Pithead one of the new neighbours was also able to accurately assess the situation: “They thought you were the big I Am……but ah could see through it. Ah could see the sadness, and ah knew ye had to be a big drinker.”

We never get told a reason for Agnes’ addiction. There is no single explanation given but the seeds are deeply sown and scene set. Her parents debate long and hard with Agnes, tales of her being spoilt and over indulged as a child.

On reading, it was only after I’d made my assumptions as a social worker that the family secret was landed unanticipated in front of me. There is tragedy and lose and, forget counselling - the family rule is it is not to talk about it. This trauma casts a shadow on everything else that follows.

To know what is going on for Agnes, we have to know what her relationships are, what meaning she brings to the family in the light of the loss and its impact on the security of relationships. Her disastrous adult relationships seem to follow from the fractured family of her childhood.

Sex permeates much of the story; desires, wishes, identity and far too often abuse. Shuggie’s own sexuality as a gay child in a brutal homophobic culture emerges with increasing resolution despite an environment of insecure masculinity and at times, the mistreatment, rivalry and abuse amongst children.

As social workers we often have to deal with the brutal reality of sexual abuse, but we remain too prudish and too self-conscious to look more comprehensively at intimate relationships. Yet if we don’t know what “good enough” sexual wellbeing looks like; we will not be well equipped to support those encountering relationship difficulties let alone experiencing sexual abuse. Stuart is much more adept at naming these realities than social workers.

Stuart illuminates the resilience and determination of each of the family members. Despite all setbacks, Agnes has a pride and determination, in her appearance and speech, in her dignity amongst neighbours and ultimately, however distorted, in her love for children.

The gender difference in the siblings’ respective routes to survival is a true depiction and of what happened in the 80s and continues (to a thankfully lesser extent?) today.

When things go wrong for families the children suffer. Shuggie is exposed at far too young an age to alcohol abuse, inappropriate adult conversations and to adult sex. Children are asked to take on far too much responsibility for their own care and for the care of the parent. They are asked to collude in the parent’s conspiratorial behaviours. Shuggie, for example, has to feign sickness when Agnes is drunk and he can’t get to school.

Stuart also knows the importance of the stories people tell to survive. We tell ourselves stories to protect our ego and sense of security, and indeed for very practical reasons. When her eldest son Leek is sought by the police for an alleged assault, Agnes defends him to the hilt. What did or did not happen was in many ways irrelevant for her.

To the social worker is she dishonest? Or is her behaviour functional in a dysfunctional environment. Social workers need not only to ask is this person telling the truth but also to consider what is the purpose of this person’s narrative (false facts anyone?)? Furthermore, we need to be aware of the purpose of our own narratives because social workers also tell stories.

Shuggie knows he is different to his peers well before he knows he is gay. In an era of homophobia and a lack of understanding of gay lives, positive relationships for Shuggie only emerge with a degree of trust when there is covert acknowledgement of who he is.

In the absence of an acceptable verbal narrative at that time, he communicates his own reality initially through play and the use toys which, of course, children do. It might appear cliched but dolls and colourful plastic ponies is what he liked.

As he gets older, gay language or narrative appears prohibited so he can only produce his own “narrative” in the way he relates to others. Social workers need to remember that children communicate through their behaviour. Shuggie first achieves conscious, tentatively spoken understanding of who he is with a female friend, Leanne.

Shuggie establishes a friendship with Leanne through caring and the fact that she accepts him for who is. This friendship is key to his survival. Despite the adversity and traumatic childhood, we have optimism for Shuggie’s future because he is able to make loving, positive relationships.

The relationship points to the fact that he is going to be okay. He is able to work out the route to his future. To use the social work parlance, he is solution-focused. He is making a new positive narrative.

Social workers have lessons to learn (need reminded of) from Douglas Stuart. The political and economic landscape directly affects children’s lives. Addiction is often a symptom of trauma, and family, however problematic, matters. Love and relationships matter.

Social workers need to understand each player brings their own (often multiple) narrative to situations and it is important for them to make sense of the function of each story.

Children can be incredibly resilient. If social work can do anything in situations of severe adversity, it is to foster this reliance and create the opportunity for children and families to repair, sustain, and secure new, positive relationships.

Social workers need to listen to and engage with those in adversity before they can ever help them affect positive change; to paraphrase humanist psychologist Carl Rogers, they need some of Shuggie’s “unconditional compassion”.

David Stakes is a qualified social worker and writer. He presently works as a children and families team leader in the West of Scotland