Social work in the shadow of Grenfell

Mariam Raja was one of the first social workers on the ground in the wake of the fire that ripped through the Grenfell tower block in Kensington last year.

When she thinks back to that time, she describes the role she performed as providing an “umbrella”, metaphorically speaking – a shelter from the storm for those affected by the worst tragedy on British soil in recent times.

“There were people who were traumatised and trying to rebuild their lives amid the chaos,” she says. “What they wanted, which is the role of the social worker, was that umbrella: someone they could pick up the phone to and speak to instead of going through automated systems, and say, ‘Hi Mariam, can you do this for me?’”

An adults’ social worker for the Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, Mariam was asked by her service manager to join the Government-established Grenfell Fire Response Team. She was initially told it would be short-term, but such was the need within the damaged and traumatised community it ended up lasting seven months.

“Early on we were trying to work out who needed to be reached: who were the service users, who were the people in the tower. We were not sure who needed the services and how we could reach out to them.

“Everyone from professionals to service users were trying to make sense of the event. In the beginning it was a blur.”

Some immediate needs quickly became apparent, such as emergency housing and replacement of documents. Others emerged more slowly.

“As the months went on and people came to terms with the tragedy, it became obvious there was a need for long-term mental health treatment. A lot of them didn’t like that term – they weren’t mental health service users before and didn’t feel comfortable with that terminology. But they needed help overcoming trauma and bereavement and understanding that.”

Mariam says she was given significantly smaller caseloads than she would normally have to manage in practice but worked with clients in a much more intense way.

“You would see someone for two or three hours at a time, holding their hands and guiding them through the process. It could be supporting people with small things like paperwork and bigger things like sitting there and listening to people who have been through trauma, using therapeutic social work methods to reach out to them and help them understand the help they need.”

Mariam says in many ways the work she did at Grenfell was a return to the kind of practice that time pressures and excessive workloads can make difficult today.

“Social work in the current economic climate sometimes leans towards assessing for services. The work we did was thinking away from the Care Act and eligibility to being able to use more of the skills we wish that we could use day-to-day.”

A key element of her work at Grenfell was listening – to individuals and the community.

“Their voice was so important. It was for the community. That sort of social work is very powerful. We constantly say the service user is in the centre of our interventions. I don’t know if that is always the case, but this did feel like it was for the community, powered by the community. And in the period of time I was working for them I felt I was part of the community. There were times that they didn’t like something we were doing and we were flexible to change it. It felt very equal, a community-led form of social work.”

Working with people so intensely against a backdrop of tragic loss and trauma took its toll on the social workers involved. Mariam believes there is an inevitability to this, the emotional cost to doing the job properly.

“I believe to be able to support them in the way they needed you have to feel their pain and embrace their trauma to fully understand it.

“Sometimes you embody that pain and upset a whole community is going through. I live in West London so it did feel like my community going through it. That does have an effect as a social worker, not early on but afterwards.”

Having the time for reflection helped, as did supervision. But most important of all was the support of other social workers on the ground who, she says, “truly understood what you were going through”.

One aspect of the Grenfell tragedy was the anger from within the community and without, directed towards the local authority and the Government, that such a tragedy could happen. Kensington and Chelsea Borough Council was accused of putting cost-cutting before the safety of residents while the fire-scotched tower block located in the UK’s richest borough became a symbol of social injustice. An inquiry into the fire and a criminal investigation remain ongoing.

“There was a lot of politics around it and there still is,” says Mariam. “I saw that in the media and heard it from the community but you can’t get caught up in all that and still be person-centred.

“You have to really focus on the people you are supporting. If you did get involved in the politics it might have hindered the work you were doing with the service user. Politically, I have my own opinion but when it came to professionally doing my work I felt I couldn’t mix the two.”

Mariam and others drafted in to support people in the immediate aftermath of the fire have now returned to their day jobs. But the pain is far from over for those affected. Nine months on, some residents remain without permanent homes. Many are still in need of emotional support to come to terms with the life-changing events.

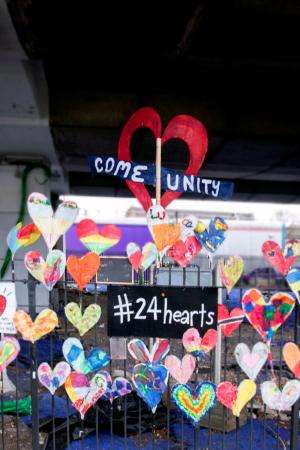

But amid all this tragedy, there were some positives, says Mariam, most notably the spirit of community and people supporting each other that also became one of the legacies of Grenfell.

“Witnessing a massive community response was a really beautiful thing to see. There were different responses from different communities but generally speaking it was an open and positive response. We saw a very close-knit community, people supported each other. You don’t always see that in London where sometimes people don’t even know their neighbours.”