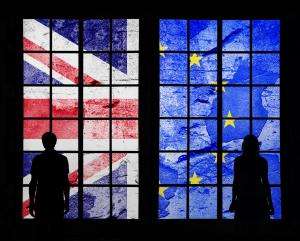

What happens to pan-European child protection post Brexit?

9 November 2018

Recent discussions surrounding Brexit have focused on how best to manage the inevitable economic loss of leaving the internal market. However, the free movement of people within the EU has resulted in a whole generation forming family relationships across national borders. Millions of children have parents and extended family spread across the EU. So if the UK leaves the European Union, what happens to these children if there are disagreements and disputes about their care?

There is considerable uncertainty about the future of family law post-Brexit. One area which has received relatively little attention is the impact of Brexit on children with European connections who are in need of protection by the state.

When a court has to determine the future of a child with European connections, there is an EU regulation, known as Brussels IIa, which governs matters relating to parental responsibility.

In a child protection context, Brussels IIa ensures that care proceedings concerning a child with European connections are heard by the correct and competent court and that protective orders in relation to children can be recognised and enforced across the EU.

Brussels IIa also provides a vital framework of cross-border cooperation and communication between member states which can, for example, enable family members overseas to be assessed as potential carers for a child and facilitate the exchange of information between authorities to protect children.

Historically there have been concerns about a lack of awareness of Brussels IIa by courts and local authorities in the UK in the context of care proceedings. In 2015, the Latvian Parliament formally complained to the House of Commons about “insufficient cross-border cooperation” in cases concerning children of Latvian decent who were placed for adoption in England. Since then, there have been moves to increase the awareness and use of Brussels IIa and it is now widely used in care cases with a European element.

So, what will happen to this important framework for cross-border cooperation after Brexit?

Brussels IIa is one of many pieces of EU law under the umbrella of ‘Civil Judicial Cooperation’ – instruments which govern reciprocal relationships between the member states in civil court proceedings. These legal agreements provide a degree of consistency in court proceedings within the European Union.

Whilst the Government will incorporate EU law into UK law through the EU Withdrawal Bill and then consider which laws to keep and which to repeal, instruments of Civil Judicial Cooperation cannot be effectively transposed in this way – reciprocal instruments depend upon the participation of the other member states. Their continued effectiveness is therefore dependent upon the UK’s future relationship with the member states.

Over a year ago, the House of Lords European Union Committee urged the Government to consider the impact of Brexit on family law. The committee was not convinced the Government had a “coherent or workable plan to address the significant problems that will arise in the UK’s family law legal system post-Brexit, if alternative arrangements are not put in place”.

However, the Government’s position remains vague. In their ‘Future Partnership Paper’, published in August 2017, the Government indicated that it wished to negotiate a “new civil judicial cooperation framework, as an aspect of the deep and special relationship with the EU”.

As part of this, the Government wants to enter into new agreements with the 27 remaining member states reflecting the terms of existing agreements (e.g. Brussels IIa) rather than using alternative instruments which do not have their origins in EU law in cases involving member states, such as the 1996 Hague Child Protection Convention (which applies in many states inside and outside of the EU).

Questions then arise about what form these new agreements will take and how issues about their interpretation will be resolved giving the Government’s apparent opposition to the jurisdiction of the Court of Justice of the European Union which oversees all EU laws.

The position is further complicated by the fact that Brussels IIa is in the process of being revised and improved so that it works better for children and families in cross-border cases. The proposed revision known as ‘Brussels IIa Recast’ is currently being considered by the Council of the European Union. We don’t know when Brussels IIa Recast will enter into force.

Will it be possible for the UK to enter into new agreements with the member states and if so what will these look like? Will they reflect Brussels IIa or Brussels IIa Recast? What if Brussels IIa comes into force after exit day but during the transition period? What will happen if Brussels IIa Recast enters into force after the end of the transition period? It would make no sense for the UK to have an agreement which mirrors Brussels IIa with the other member states, but for those member states to use Brussels IIa Recast with each other. So long as these questions remain unanswered the future status of thousands of children caught up in cross-border legal proceedings remains unclear.

In the event of a ‘No Deal’ Brexit, the Government has said that the UK will fall back on using a non-EU instrument - the 1996 Hague Convention. If this occurs, then there needs to be training and awareness about the differences between the two instruments, differences which are subtle yet important for professionals working to protect children involved in cross-border disputes.

Brexit raises complicated issues about the future for the UK in many economic areas. But the daily lives and futures of thousands of families will be affected by the decisions which are taken. Clarity and certainty are urgently needed to ensure that professionals and courts can work together across borders to protect children with international connections.

Maria Wright is a legal adviser to Children and Families Across Borders, the only non-government organisation in the UK with a dedicated inter-country social work team to deal with children and families cases involving the UK and one or more other countries.