SWU Campaign Fund update: Rampant food insecurity hitting most vulnerable

The campaign group Food is Care is being supported by the SWU Campaign Fund, run in conjunction with Campaign Collective.

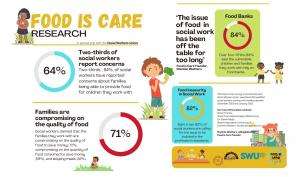

The figures from the Food Is Care survey (December 2021 – January 2022) have uncovered a scale of food poverty and insecurity not seen before. According to the new research, two-thirds (64%) of social workers have reported concerns about families being able to provide food for children.

Social workers interviewed by the group claimed that families they work with are compromising on the quality of food to save money (71%), compromising on the quantity of food consumed to save money (59%), and skipping meals (55%).

Over four-fifths (84%) said the vulnerable children and families they work with rely on food banks.

Over the past 12 months over half (52%) report food poverty and insecurity has got dramatically worse with a further 35% saying it has got somewhat worse.

Click here to see a full-sized version of this infographic of the Food Is Care survey results.

Dominic Watters, a single dad social worker who runs the Food Is Care campaign, said, “The issue of food has been off the table for too long because social work leaders are out-of-touch with the daily living experience of poverty. Food is Care is a campaign letting those in power know that poor, often single parent families in council estates, are hungry and feel unheard.”

John McGowan, General Secretary of the Social Workers Union, commented, “Independent foodbanks continue to pick up the pieces yet again as more and more people struggle to pay the bills. There needs to be a realisation that we cannot continue to provide an emergency response to a long-term crisis.”

The pandemic has brought the hidden struggles of many experiencing food poverty to the fore. It is the reality of life for millions of people. The time is right for this vital Food Is Care campaign to make the case for the right to food to be realised by all, and SWU alongside Campaign Collective proudly supports them in this message.

One social worker, responding to the survey, told researchers:

Food poverty is rampant.

Another commented:

Food insecurity and hunger on our youngest children whilst they are developing their brains and attachment has a life-long effect – many of our looked after children have significant issues with food as a result of the poverty, neglect and lack of good enough care including food despite being removed into care and moving on to better family life.

Another social worker added:

I have been horrified to become aware of the number of people in work but needing to use food banks because they can’t keep warm and eat. What a way to live!

Despite the extent of the problem revealed by the research only a few social workers (6%) felt they had sufficient training to deal with the issue. Eight in ten (82%) added that the issue should be included in the British Association of Social Workers’ Professional Capabilities Framework, Department of Education Knowledge and Skills Statement, and Social Work England’s professional standards.

Dominic Watters continued:

“Our unique survey not only shows how widespread this issue is, but also an undeniable connection between food insecurity and social work.

“I am asking for the professional bodies to view this as an opportunity to centrally locate food insecurity into their practice guidance to help address this inequality.

“The fact it is taking a single dad from a deprived council block and not the policymakers to request this change is-in-its-self a demonstration of the discrimination poor people experience.”