‘Children know when you are interested in them as a person’

Published by PSW Magazine, 09 June 2023

Foster children, says Fran Hill, have to navigate all sorts of differences as they adjust to life in their new home.

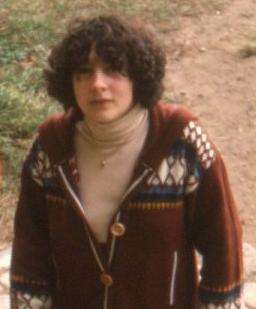

She speaks from experience, having being in foster care herself in the 1970s, a period of her life she draws upon in her novel, Cuckoo in the Nest.

The story is set in the heatwave of 1976 and focuses on Jackie Chadwick who is placed in a foster home that she soon discovers is decidedly dysfunctional.

Fran put a lot of herself into Jackie: “Looking back, I didn’t realise how hypervigilant I was as a teenager. I grew up watching other people, sitting at the edge of the room… I wanted to instil this in Jackie and have her watching.

“She’s very attuned to emotions. She observes and tries not to get involved. She watches other people going through emotions, she’s really got antennae where the foster family is concerned. She knows what's going on in the room. And I really liked that about her.”

Fostering is a massive adjustment for the foster family, too, Fran adds. “Foster families don't know how much they're prepared for the fact that a child is going to change your family as much as you are going to change that child.

“You can't drop a boulder into the middle of a pond and not expect waves.”

Speaking about why she went into care herself, Fran says: “I was born to a teenage mum, who already had a drink problem at a very early age.

“She was 17 when she had me, and I guess that in a way, she never really had a chance because she was already very ill.

“She had four children by the time she was 22. My dad was in the army and so we were living in barracks and moving from place to place, and she just wasn't coping.

“We had a very nomadic life and he left when I was eight.

“That’s when things got worse. There were unsuitable men in the house with me and my two sisters. And from that stage, we began to go to temporary foster placements.

“There was a placement, the one I base the book on, when I was 11 or 12. I don’t remember why I was there, or why I left.

“And then, when I was 14, I went to what was supposed to be another temporary foster placement, but it became permanent because my mum died three months into it, so I was with them till I was 18.”

As a teenager, Fran found it hard to apply herself at school and left to work in a factory despite the offer of doing A-levels at college. She returned to education later in life, gaining a first-class degree in English Literature and becoming a teacher. In the last two years of her career she worked in a Pupil Referral Unit, where she regularly encountered children with additional or complex needs.

Her own experiences in her teens helped her understand some of the issues her pupils were facing.

“Some children, you'd know that they were particularly vulnerable with very difficult home lives, but they worked like Trojans, sat in the classroom, got their heads down, tried to ignore what else was going on, because you could see how desperately they were trying to make the most of their education.

“Then you had the others who just couldn’t cope in the classroom, who were completely dysregulated. I really recognised myself in those children because that's how I was, a complete and utter pain to my teachers.

“But the role of the sensitive teacher is to be aware of why that child might be playing up.

“I really tried to connect with those children, to gain their trust so that they knew you actually cared. They can be won round with enough attention from somebody who sees the potential in them.”

Writing a novel is essentially a creative act where you build characters in a fictional world. But Fran says she has fragments of memories from her time in care, particularly from the placement when she was eleven, that sparked ideas.

She explains: “I didn't have many facts to go on. All I really had was that they had a Dalmatian dog and that there was a girl there around my age. That's what really fascinated me, thinking about her and how she may feel about me arriving. There was a particular dynamic to explore.”

What fascinated Fran in writing her novel is how the family unit within a foster placement is potentially disrupted, how they face their own upheavals, as well as the child placed in their care.

She believes that foster carers shouldn’t be seen purely as rescuers. They are complex family units already, with their own baggage.

Fran says: “To what extent do people keep their secrets? That’s what I wanted to explore - the fact that this family that take on Jackie have their secrets, and her very presence is the catalyst that weeds those secrets out.”

The experience of arriving in a new home as a fostered child is also something Fran describes in Cuckoo in the Nest.

“It’s such a massive moment, isn't it? And from my point of view, while I don't remember the actual arrival at my temporary placement – the one that inspired the book - I do remember the arrival at what became my permanent foster family.

“It was just this sense of shock that their house is so different. There was also a sense of displacement, of restrictions, unfamiliarity with other people's routines.

“In the book, Jackie thinks she’ll get a good night's sleep on her first night, but there are creaks on the stairs and the boiler making noises and all this new stuff to get used to.”

Fran says a lot of the issues for her when she was fostered were about adjusting to stability, normality, after a chaotic upbringing.

“My foster parents seemed to me so straight and boring. It was all so alien, and I really kicked against that. They were doing their best I think, to put in some structure and routine. But compared to before with my mum, where I was basically doing what I wanted when I wanted, to actually have people saying you've got to come in at this time and do your homework… I didn't give them an easy time.”

She is ultimately interested in what leads people down the fostering route in the first place, and this is explored through the family in her novel: “What was their motivation for fostering? I wonder to what extent they thought it would paper over some cracks. You know, that really does interest me.”

Fran has largely good memories of the social workers she encountered in the 1970s. What is most striking about her recollections is the time and freedom they had, compared to today.

She says: “They were really kind. I remember things that probably wouldn’t happen now. There’s a hotel at the top of Kenilworth, and I remember going there with my social worker for a cup of tea, and we'd been there for a couple of hours, just very relaxed.

“I also remember going to the house of another social worker, where I had fun playing with her little children. There must be so many things that would militate against that now.”

Even the scant notes she’s encountered from those days (Fran asked to see her records and found much had been redacted) reflect time spent on the frontline rather than chained to a desk.

“If you just look at a set of notes from the 1970s, and the sort of the records that social workers had to keep, you're talking individual sentences, a couple of jotted notes, and that was it for that visit, then they would go and see the next person.

“I have spoken to social workers I know in various sectors and they tell me 80-90 per cent of their time is spent on the computer. I just don't see the logic of that.”

While she didn’t set out when writing the book to impart a specific message, on reflection, Fran says, a message has certainly emerged.

Her plea is for all those working in the fostering process to be more trauma-informed and for more resources to be put into the care system.

Fran underlines, from her own experience, the need to really understand what it is for an already traumatised child to encounter more trauma in the huge change that foster care brings.

“A new foster home alone is not going to deal with the traumatised child. In fact, a new situation or a new family may even make things worse for a while,” she says.

“There needs to be a strong focus on the effects of trauma, and support for the child as they deal with that as well as a new situation. There also needs to be better support for the children who are already in the foster family… my novel very much looks at sibling rivalry.

“We need to at least have social workers and foster carers who are trauma aware, even if the resources aren't there. If the awareness is there, that has to be a big part of it, as it is for teachers and in the police.

“Ultimately, of course, it's a false economy not to apply more resources because doing so has a huge benefit later down on down the line. In five years, being trauma-informed could make a complete difference to this child. It could help them get through education, get a decent job, and be a really solid member of society.”

Returning to what she learned as a teacher, Fran says: “Everybody has their talents and gifts and it’s about getting some support to follow some kind of passion that makes you feel good about yourself. Everybody's got something.

“I think children know when you're interested in them as a person, not just as a foster child, or as someone who's doing exams, but in who they actually are, in their core being and I think the problem when things are under resourced is that it depersonalises the whole thing.

“It ends up with the child being the case, rather than a person. It’s the same in teaching, in the police, and in the NHS. You get reduced to the case rather than the human and that's really dangerous.”

Fran Hill is a former English teacher turned writer. ‘Cuckoo in the Nest’ is her first full-length work of fiction. Her previous book, a memoir of a year in her life as a teacher, is called ‘Miss, What Does Incomprehensible Mean?’ and was published in 2020.