Social Graces: A practical tool to address inequality

On January 1st 2020, if you had asked the average social worker whether they operated in a fair and just society, the resounding answer would have been ‘no’.

Not after a decade of austerity, which saw poverty skyrocket to 1.2 million up from 41,000 in 2010. And certainly not after the referendum, which saw 71% of ethnic minorities reporting racial discrimination, compared with 58% in January 2016 before the EU vote.

If you asked the same question today, on 29th June as we approach the half-way mark of the year, the answer would be unequivocal. There is no question that the coronavirus has widened the schism between the rich and the poor. Coronavirus deaths are doubled in affluent areas compared with the most deprived.

Beyond our own shores, global events remind us that equality is but a distant dream. George Floyd’s last words, as he was murdered, will haunt us forever. ‘I can’t breathe’, he said.

As the minutes passed by, George reverted to system of hierarchy, to appease his killers. He began to use language such as ‘Sir’, addressing those who harmed him as though they were his superiors.

This interaction speaks volumes of institutionalised racism. No matter what platitudes we learn about equality and diversity at school, or in the workplace, it is clear that not everyone begins the marathon of life on the same footing.

Whilst some race forward in streamlined running shoes, unaware of the privilege lurching them forward, others are glued firmly to the starting line.

Ethnicity, class, disability or gender hinder their progress from the first millisecond of the race. And few can, no matter the amount of hard-work, realistically, close that gap.

It is easy to think:

“But just because I might conform to privilege, it doesn’t mean I’ve had it easy”.

And this is true. Human suffering is ubiquitous. But do you dare to ask yourself the following?

• Have you ever been rejected from a job application solely based on your surname?

• Has a disability ever prevented you from contributing to the workplace?

• Have you ever felt too intimidated to disclose your sexuality to colleagues?

• Have you ever been overlooked for a promotion because of your gender?

We need tangible tools we can use to fight against prejudice, to acknowledge privilege, and to redistribute power. The Social Graces is one of the tools which can help us to achieve this.

What are Social Graces?

In order to get to grips with the Social Graces tool, I consulted with Rowland Coombes, a family systemic psychotherapist, and a clinical lead at the Centre for Systemic Social Work.

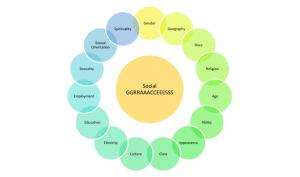

[Figure 1 – NES].

Power imbalance

The term ‘Social Graces’, Rowland explained, is a mnemonic to help us remember some of the key features that influence personal and social identity (see figure 1), as developed by John Burnham, Alison Roper-Hall and colleagues (1992).

Originally, the pneumonic was arranged as ‘disgraces’ to highlight the fact that such inequalities were ‘disgraceful’, but it was feared this could be rather off-putting. So, over time, the ‘dis’ was dropped, and the ‘social’ added to the front, to highlight the fact that the graces have an impact not only on an individual level, but are activated within the community.

One of the key aims of the graces is to ‘name’ power differentials. In doing so, it is far easier to identify (and work on) our own prejudice, or indeed on our own privilege.

Naming power differences can invite service users, colleagues or even friends to share the social graces which they feel can hold them back, or even cloud their judgement of others.

The graces in the figure about are not an exhaustive list, and can be adapted. They could differ according to place, time and culture. That’s the beauty of the graces; they are fluid. There is room for reflection and correction.

What Rowland says next is music to my ears – especially as someone who understands the pressures on social workers to produce Ofsted-pleasing statistics, reach targets, and tick the boxes required for inspections:

“The graces are about process, not procedure. It’s about the interaction between people, not data.”

For most of us, it is people, not spreadsheets, which ignite our desire to become social workers.

The social graces align with the BASW 80:20 campaign, which champions relational practice, with the desire to reverse the ratio of social workers spending 80% of the time at their desks, and just 20% with service users.

Ecology of mind

Putting the need for the social graces into a cultural context, Rowland explained that in our western, capitalist society, we have often tended to think of ourselves first and foremost as individuals, rather than as a cohesive unit.

This resonated with me on a number of levels; I only began to understand the self-centric nature of Western culture when I lived in Chile, where the first question asked to a stranger was not the typical ‘What do you do for a living?’, but ‘Tell me about your family’.

The social graces, however, recognise that we are not isolated beings. That there is such a thing as society –despite messages to the contrary which have seeped into our national psyche.

Rowland said:

The social graces remind us that we are like fingers which, whilst moving independently, are connected. If the tendons in one finger are strained, and it becomes less mobile, there is likely to be an impact on the others.

I like this concept, because it removes the urge to ‘pin down the blame’ on one individual; social work is rife with blame culture. Because the stakes are so very high. Because we fear the potential consequences should things go wrong.

In moving away from personal culpability, we begin to humanise each-other. To separate challenging or problematic behaviours from the individual (whilst not absolving them of responsibility).

How many times as a social worker did I hear the dreaded phrase ‘He/she is a challenging child’. Well, that’s simply not true. The child is not problematic. But there is something inherently problematic about labelling and stigmatising.

The Social Graces challenge the idea of a ‘fixed personality’. Think about it for a second. Are you the same person around your partner, your cat and with work colleagues you meet for the first time? No. As human beings, we feed off the energy and discourse of others.

Applying this to the example above, the Social Graces can help us to understand the child in the context of their relationships.

How to use the Graces as a time-pressed social worker

• Choose one of the graces you are drawn toward. Or ask service users to do so. Reflect on why this is – this is something you can share vocally, through writing, or any other creative outlet.

To get you started, here is a personal example:

I have selected ethnicity as a grace I am drawn toward.

As someone who is dual-heritage, but cloaked in white privilege due to my light skin tone, I am painfully aware of power differentials in terms of ethnicity; I have, throughout my life, been given different treatment to other family members.

I have no reason to fear the police; my dad does, and has been assaulted by them.

I was always encouraged to achieve my full potential at school; my dad wasn’t, and was bullied and humiliated by teachers.

I have travelled around the world with no fear that I would be singled out for my skin colour; my dad, on the other hand, is too fearful to travel to America for the fear of being attacked.

I have always been referred to by my first name at work; my dad, on the other hand, has been called by racist nicknames which have ‘stuck’.

I feel stuck between two worlds, in that I have been treated as a ‘white’ person my whole life, yet witnessed indirect racism throughout my childhood.

- Attempt the above exercise with the grace you feel the least drawn toward.

- Consider which of the graces mostly influences your relationship with a service user. Or a supervisor/supervisee. This may feel uncomfortable at first, but keep at it.

- Rate the graces on a linear scale of 1-10, 1 being that they impact you only a little, 10 being that they impact you significantly. This is also an exercise which can be done with service users, both adults and children, to learn more about the way in which they see the world.

• In a group setting, or in pairs, attempt to roleplay the social graces from different perspectives.

This article serves only as a brief introduction to a tool which is far richer and deeper than has been outlined here.

To learn more about the Social Graces, further detail can be found below – I hope they serve you well in your journey of self-reflexivity and change:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2005.00318.x

https://www.camdenchildrenssocialwork.info/blog_articles/1967-first-systemic-concept-clip-live