Purpose

This section of the Capabilities Statement is based on the Purpose ‘super domain’ of the PCF, which is about ‘Why we do what we do as social workers, our values and ethics, and how we approach our work.’ (BASW, 2018; p. 4). Within the PCF, this includes the domains 2 – Values and Ethics, 3 – Diversity and Equality, 4 – Rights, Justice and Economic Wellbeing.

Key messages

The foundational values of social work with autistic adults are recognising, appreciating, and promoting the values of neurodiversity. Within the community of autistic people, the label or category ‘autism’ is rejected by some and accepted by others. Social workers should know how people describe themselves and their self-identity.

The purpose of social work is supporting autistic adults to identify their needs and communicate how autism distinctly impacts on their everyday lives. Social workers should understand the impairmentsthat people can experience from the impact of autism and work with them to address them.

Social workers should underpin their work with principles of personalisation. This means acknowledging and welcoming the abilities and creativity of autistic adults, whilst understanding how autism impacts on them individually, and within their social and online networks.

Recognising individuals’ strengths and empowering them

As a ‘spectrum’ of conditions, autism impacts uniquely on each individual. This may be visualised as a continuum – at one end, individuals need minimal support whilst others at the other end of the continuum, may need high levels of care. However, it is recognised that autistic adults have strengths – for instance autistic adults involved in the development of this Capabilities Statement identified their strengths as: creativity, understanding and adhering to routines, knowing detail, ability to occupy themselves through routinised leisure activities, and awareness of stimuli within their immediate environment.

Therefore, social workers should operate within strengths-based approaches, starting from the position that autistic adults have abilities.

The focus should be on individuals’ strengths and abilities and not deficits. However social workers should also recognise that the strengths gained from autism can result in each autistic adult needing specific assistance, depending on contexts such as their personality and family circumstances (O’Dell, 2016). Social workers should therefore involve autistic adults in (self) identification of their strengths.

The above also involves supporting and empowering autistic people to maximise their ability to identify their life choices (and preferences) and to make decisions about all aspects of their lives. These include routine activities and life-changing events (places of residences, social networks and relationships, education, and health and social care).

Autistic adults involved in developing this Capabilities Statement urged social workers to start each conversation with them with the statement ‘what are your priorities today?’ This formulation will enable autistic adults to lead the discussion by identifying their preferences.

Social workers should:

- Ensure that their work with autistic adults is underpinned by principles of personalisation. This means holding the individual at the centre of practice, working with them to identify their unique abilities and challenges, and working alongside them to achieve their (self) identified needs

- Understand strengths-based approaches to social work (Baron et al, 2019), reflecting on their applicationto practice with autistic adults

- Focus on what individuals can do and reflect on their assumptions about how autism impacts Promoting the human rights and dignity of autistic adults

Autistic adults experience uneven access to the human and welfare rights enshrined in law. For instance, the Care Act 2014 and accompanying statutory guidance (DHSC, 2018) stipulate the right to assessment, however autistic adults involved in the development of this Capabilities Statement reported reduced realisation of this right. To prevent discrimination in the workplace and increase the employment opportunities of autistic people, employers are required to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ for autistic people.(National Autistic Society (NAS), 2016). However their rate of employment remains low.

Most autistic adults want a job and where in part-time employment, they want to increase their hours, however 48% those in employment, involved in a survey by the National Autistic Society (2016) reported bullying. During consultation with autistic adults to develop the Capabilities Statement, they reported impeded access to the same right to support and social relationships experienced by neurotypical adults.

To contest discrimination and stigma, social workers should adhere to The Code of Ethics for Social Work (BASW, 2014), seeking to protect the human and legal rights of autistic adults, ensuring social justice for them. Social workers should champion the human rights of autistic adults – for example, right to family life, enjoyment and experiences of sexuality and sexual lives, and their right to choose their friendship networks. Peoples’ right to make ‘unwise decisions’ should also be respected.

Social workers should:

- Understand how the Care Act ‘right to assessment’ applies to autistic adults who may have needs that require provision of services. Social workers should also know about human rights and understand the laws on rights to parenting, welfare support, health care, and employment

- Understand the distinct oppression and discrimination experienced by autistic adults

- Ensure that they listen to autistic adults, recognising that they are ‘experts’ about their needs and the barriers they face in fulfilling their rights and entitlements.

Promoting self-determination, advocacy and anti-oppressive practice

Advocacy is the action that social workers undertake to protect and promote peoples’ human rights, access their rights and pursue their goals. The principle of self-determination (BASW, 2014) also requires social workers to engender the conditions which enable people to ‘speak up’ for themselves. An important component of social work with autistic adult is therefore enabling and supporting self-advocacy as this generates opportunities for people to identify their own needs, articulate their viewpoints, and challenge professionals, including their allocated social worker and/or what they want from social work. During the consultations to develop this Capabilities Statement, an emergent theme was the need for social workers to involve another autistic self-advocate in initial home visits. This will increase trust and understanding between them and their social worker.

Social workers should understand the distinctive forms of discrimination experienced by autistic adults who have other characteristics also associated with disadvantage and discrimination.

Research evidence from the United States suggests that black and minority ethnic (BAME) people receive later diagnosis (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al, 2019) than the majority white population. This can delay preventative work or early intervention. Some non-Western cultures do not have equivalent translations for the term ‘autism’, making it difficult for people to describe their condition or navigate services (Hussein et al, 2019).

Social workers should deploy their professional knowledge, power and legal status to advocate and challenge oppressive practices (Tew, 2006). The latter may include scrutinising the commissioning of services for autistic adults and supporting the development of accessible and appropriate services.

The third aspect of this capability is that social workers should enable autistic adults to access the independent/specialist advocacy services enshrined in the Care Act 2014, the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Liberty Protection Safeguards) and the Mental Health Act 1983.

Social workers should:

- Understand different models of advocacy and attain the knowledge, skills and confidence to challenge professionals (including their colleagues) where necessary

- Promote self-advocacy as a starting point of their work with autistic adults and develop their professionalskills to advocate effectively on behalf of autistic adults

- Understand the Equality Act 2010 and other legislation through which discrimination and unlawful practicescan be challenged by autistic adults themselves and by professionals, including the impact of multiple oppressions and inequalities.

Practice

This part of the Capabilities Statement focuses on the knowledge and skills required for effective social work practice with autistic adults. It is based on the Practice ‘super -domain’ of PCF - ‘What we do – the specific skills, knowledge, interventions and critical analytic abilities we develop to act and do social work’. (BASW, 2018; p. 4). (NICE) includes the PCF domains: 5 – Knowledge; 6 – Critical Reflection and Analysis; 7 – Skills and Interventions. It should be cross-referenced with the Knowledge and Skills Statement for Social Workers in Adult Services (Department of Health (DoH), 2015).

Key messages

Social workers can co-create positive changes with autistic adults through relationship-based practice underpinned by sound knowledge about how autism impacts on people, theories of social change and commitment to ethical practice.

Social workers should focus on peoples’ needs and strengths, and not diagnosis alone. Some people may show signs of autism and yet not want to be diagnosed, while others may find diagnosis beneficial. Social workers should contest any situation in which a diagnosis and identification of autistic is used as the gateway to services.

An important social work aim should be preventative work. Regular health assessments can ensure the identification of co-occurring health conditions, stopping worsening physical and mental health of autistic adults. Including sensory needs and ‘triggers’ of crises in all assessments can reduce behaviours whose management challenge professionals and carers, and co-production of de-escalating plans of crises can prevent involvement of coercive psychiatric treatments.

Understanding autism and co-existing conditions

Social workers should understand the signs of autism and its impact on individuals. This includes recognising that the:heterogeneity of impairments, strengths and co morbid conditions necessitates a wide range of support. While some individuals need little or intermittent support, others require substantial daily support. Similarly, carers may also have their own support needs.’ (D’Astous et al, 2014; p. 791).

Social workers can increase their knowledge about autism through regular training, however in their everyday work, to attain holistic understanding of the effect of autism on individuals’ needs and develop corresponding personalised care plans, social workers should do direct work with autistic adults and their carers; and work in partnership with allied health and care professionals (National Institute of Care Excellence, (NICE) 2016). Some autistic adults may also resist diagnostic labelling and it is therefore important that social workers know how autism might manifest in peoples’ health, social, and developmental needs.

There is evidence that the presence of autism signals other health issues, this means that autism and other health conditions can exist simultaneously.

Autism and common co-occurring conditions

- Anxiety disorders, which may be caused by autistic adults ‘concerns about disruptions to their routines’ (Gaigg et al, 2018).

- Eating disorderssuch as bulimia, over-eatingor avoidance of food (Harper et al, 2019)

- Epilepsy – please see ‘Epilepsy and autism’on website of Autistica

- Learning disability - It is estimated that Around 4 in 10 autistic people have a learning disability.’ Autistica website.

However, other medical issues may not be recognised through ‘‘diagnostic overshadowing’, a process by which physical symptoms are misattributed to mental illness [or disability].’ (Jones, 2008). Thus, professionals can sometimes misrepresent physical and mental illness in autistic adults as symptomatic of autism and therefore not address them.

The social worker’s role is vital. Social workers should prioritise needs assessment, instead of diagnosis alone, focusing on peoples’ strengths and the impact of any condition on their everyday functioning through person-centred assessments and care planning (as stipulated) in the Care Act. During diagnosis, social workers should advocate for the assessment of other co-occurring health conditions (NICE, 2014). Through (self) advocacy and multi-agency working, social workers should ensure that autistic adults have regular medical check-ups.

Social workers should:

- Seek to work in partnership with individuals to understand how being autistic impacts upon them daily

- Access Continuing Professional Development (CPD) opportunities toensure their knowledge about autismand co-occurring conditions remaincurrent and relevant to social work practice

- Understand that not all adults showingsigns of autism will have or desire a medical diagnosis. Social workers should focus on addressing peoples’needs through multi-agency assessments and self-identification of social and health needs taking account of family and carers’ views where appropriate, instead of pursuingdiagnosis as an end goal.

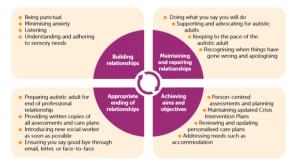

Developing relationship-based approaches

In the consultations with autistic adults to develop this Capabilities Statement, they explained that their experiences of their first meetings with the social worker are likely to shape the rest of that relationship. They noted that:

- Home visits by social workers cause them anxiety, and this is amplified if they are parents, because they fear that their children ‘will be taken away’. This can lead to ‘catastrophising’ – ‘Because of this high state of anxiety, many autistic people find that their brain goes straight to worst case scenario in a variety of situations.’ (MacAlister, 2017). The level of anxiety maylead to some autistic adults being unable to verbalise their thoughts

- Stemming from the anxiety caused by visits,autistic adults demand punctuality and consistency; and they require social workers to fit into their routines, instead ofbeing required to adhere to schedules primarily designed by their social workers.

The above means that a key aspect of relationship-based practice with autistic adults is preparation for visits and minimising anxiety. This involves learning about the person, making preparations for introductions, including considering the environment and any sensory difficulties, alongside the social worker providing their photographs and agenda for discussion ahead of the visit. Communication through text message or email may support the beginnings of this relationship. Some autistic adults prefer interacting with professionals online because this minimises outside stimuli, which can overload them sensorially (Bertilsdotter Rosqvist et al, 2013).

The practical steps that social workers should adopt in a relationship-based model with autistic adults are: openness, honesty and transparency, building trusting relationships; agreeing the aims of work and how this will be achieved, punctuality; consistency and familiarity such as maintaining a similar appearance, outfit or hair style, as this can support relationships to develop.

Social workers should:

- Ensure that they minimise any anxiety that may be caused by their professional status and their home visits. Autistic adults advise the following to minimise their anxieties:social workers writing ahead of theirvisit to explain their role and purpose,being punctual, respecting their sensory and communication needs, and modelling ‘good’ behaviours

- Display professionalism and use supervision and other sources of support to critically reflect on behaviour conducive to maintaininggood relationships

- Seek regular feedback from autistic adults and their carers; their own colleagues and managers about theirapproach and practice, and act upon it.

A model of relationship-based practice with autistic adults

Assessment, support, and care planning

In the Care Act 2014 an assessment is a ‘critical intervention in its own right’ rather than ‘a gateway to care and support’ (DASH, 2018). This means that autistic adults have a legal right to assessment of their needs. However, social workers may be involved in different kinds of assessments for autistic adults. They may be part of the process of diagnosis – for instance signposting, participating in the multi-agency assessment and/or supporting people during and after diagnosis (Casey and Eastwick, 2011). Social workers may also be involved in needs assessment, mental health and capacity assessments, or assessing behaviors that other professionals or carers cannot manage (NICE, 2018).

Assessment and care planning should always involve the autistic adult who needs services, and where possible it should be led by them. For the reasons discussed under ‘Developing relationship-based approaches’ assessing the needs of autistic adults may take longer than other adults as the social worker needs to understand the peoples preferred method of communication and the distinct manner in which their autism impact on them. Social workers should embrace the importance of dialogue between themselves and autistic adults and develop shared understanding of their needs. Due to the time required to conduct appropriate assessments, managers need to allocate the requisite timescales for assessments.

In completing social work assessments, appropriate planning and environmental factors are important considerations. Autistic adults benefit from clear processes and preparing them for the visit or meeting is essential. This may include sharing photographs of the venue, providing copies of questions or the assessment framework in advance to reduce anxiety.

It is essential for social workers to prepare for assessments by gathering all available information about the autistic adult. This is because the person may:

- have limited communication skills andunderstanding, therefore social workers should use assistive technology where necessary

- feel uncomfortable having aconversation with a ‘stranger’ and tominimism this, social workers should understand peoples’ styles of relatingto others

- not understand who the social workeris and why they are visiting them. This means that social workers should clearly explain their role, emphasizing their statutory duties and professionalCode of Ethics

- not be able to define what their own needs are and to overcome this, social workers should speak to friend andfamily carers who can explain what they need

- not be able to talk about or explaintheir needs very easily, and so riskmisrepresenting what they want (or need). A simple method of checkingwith the person and allowing them tocomment on assessments can ensure accurate representation of their needs

- although the person can speak fluently, but may mask difficulties with actualunderstanding. Social workers should cross-check information with carersand other professionals

- try to say the ‘right’ thing in responseto the social worker’s questions ratherthan stating what their actual needsare. Therefore they should beempowered to ‘speak up forthemselves’ and be assured that they have a right to self-determination

Adapted from Sakai and Powell (2008)

Assessments should aim at assisting people to live within their communities and maintain their existing beneficial social networks. High quality care planning and appropriate support services are essential to ensuring that people can stay in their homes safely. Focusing on people’s strengths and safeguarding; assessments should also consider any trauma that an autistic person may have experienced.

Social work assessments require skills around curiosity and questioning. For example, when working in partnership with an autistic adult it is essential to look beyond a basic questioning approach. In asking someone whether they can do their food shopping, the answer may be yes, however further exploration of how they do so may show support is required. Thus, good assessments require good interpersonal and relationship-building skills, empathy and curiosity, knowledge of relevant theory, law and evidence; and reflection.

Social workers need to be creative by using communication aids and assistive and digital technologies to engage with the person, where appropriate. Assessments should be conversational in tone and should be informed by strengths-based approaches focusing on people’s abilities, their capacities to resolve issues in their lives, take decisions, and express their wishes. Assessments should identify strengths that may lie in their social and support networks, focused on independent living and self-determination.

Care planning should aim at ensuring that autistic adults enjoy the same quality of life as everyone else – for example, access to suitable accommodation, employment, recreation and leisure; fulfilling their right to family life, participation in society, sexual relationships, and meeting of peoples’ cultural and religious needs.

Social workers should:

- Develop their skills in strengths - andrelationship-based assessment and care planning, rooted in partnership and creative conversations

- Support autistic adults to prepare for assessments by giving them advance notice of the items for discussion

- Ensure that care plans are rights-based, enabling autistic adults to exercise their right to self-determination; to live well and safely in the community

Responding to the sensory and communication needs

‘Many people on the autism spectrum have difficulty processing everyday sensory information. Any of the sensesmay be over- or under-sensitive, or both, at different times. These sensory differencescan affect behaviors, and can have a profound effect on a person’s life.’ (National Autistic Society) (wow.autism.org.UK/about/behaviors/sensory-world.asps)

Some of the autistic adults involved in developing this Capabilities Statement advised that they have heightened sensory awareness, and this can cause discomfort or pain – for example the sound of hand dryers, smell of perfumes, the sounds of shoes clipping on the floor. Difficulties in sensory processing may mean that an autistic adult has a strong revulsion to some stimuli, or that they continuously seek some sensations to fulfil their sensory needs. Sensory difficulties may also be caused by alterations to environment that autistic adults are used to – for example, different meeting venues or unfamiliar settings (for instance hospitals). Unaddressed sensory needs can profoundly impact an autistic adult – for instance they may lead to display of behaviors difficult to manage – people may become overwhelmed and cannot control their actions - or difficulties in (non) verbal communication.

Social workers should understand peoples sensory needs by asking them and professionals involved in their care.

It is also known that ‘abusive or restrictive social environments’ can cause behaviors that are difficult to manage (NICE, 2015), and that where people are under-stimulated or have limited social interaction, they may display behaviors which attract attention to their needs, but are nevertheless challenging to manage. By this understanding, behaviors that is challenging to manage can be caused by environmental factors and not necessarily by autism and/or other related conditions. Therefore, in care planning, social workers should ensure that autistic adults have the space to express their repetitive behaviors safely and they do not feel unduly constrained.

Similar to the above discussion, social workers should understand how autistic adults who they work with communicate – for example unusual or out-of-character behaviors may be a signal for sensory overload. Social workers should use different communication methods: writing letters, emails, etc; visual aids, and assistive and digital technologies. Communication should cover one matter at a time to avoid confusion, and should be devoid of assumptions, metaphors and jargon.

Communication with autistic adults should be underpinned by professional values and ethics, such as empathy, empowerment, understanding, and the right to self-determination. Social workers should be mindful that compared to autistic adults, they have more power because of their legal status and their roles (Boaten and Wiles, 2018). They should exercise this power ethically by working alongside autistic adults, taking a needs-led instead of service-led approach.

Social workers should continue to develop and reflect on their generic communication skills in practice. They should also know when specialist communication aids and assistive technology are required. When working with autistic adults from different cultures, social workers should consider working with self-advocates from their communities or using translators (NASH, 2014). However, this should be carefully planned to respect the routines and sensory needs of the autistic adult.

- Social workers should: lInclude the sensory needs of autisticadults in their assessments; they should develop and update ‘sensory profiles’ and plans to appropriately adjust the environments of autistic adults

- Understand peoples’ preferred methods of communication, including how unaddressed sensory needs can impact on interaction andretention of information

- Reflect on their skills and capabilitiesin communicating with autistic adults and/or meeting their sensory needs

Partnership working and co-production

In the Care Act 2014, co-production is defined as ‘when an individual influence the support and services received, or when groups of people get together to influence the way that services are designed, commissioned and delivered.' (DASH, 2018). In social work with autistic adults, this means ensuring that they are involved in all decisions about their care, support, and service provision, and both the social worker and the autistic adult (and their family) ‘doing the work together - from start to finish.’

Practical examples of co-production preferred by autistic adults who participated in the development of this Capabilities Statement include: the addition of their self-assessment of their needs in social workers’ assessments and care plans, being given drafts of assessments and care plans for feedback and corrections; and autistic adults setting agendas and leading discussions at meetings (at home or with professionals). Co-production can be attained through open and transparent relationships between social workers and autistic adults based on trust and mutual respect, and a commitment from social workers to empower autistic adults. This approach also recognizes that autistic adults have expert knowledge to improve services.

Social Workers should:

- Understand co-production – the principles and practice applications

- Ensure inclusion of autistic adults in assessment and all aspects of their care planning

- Engage in critical reflection to explore the application of values of co-production in social work practice and apply learning to improve interventions.

Supporting and maximizing decision-making capacity

Social work with autistic adults should be underpinned by the five principles of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MAS), meaning that:

- Autistic adults should be assumed to have mental capacity to make their own decisions, unless there is contrary evidence

- They should be supported to make their own decisions before any assessment of cognitive capacity is conducted

- The right of autistic adults to make ‘unwise decisions’ should be respected

- Where necessary, all decisions taken on behalf of autistic adults should be in their best interest

- All interventions – for example during crises – should be based on the ‘least restrictive’ principle.

When assessing the mental capacity of autistic adults, social workers should understand the impact of autism on cognitive capacity – for instance on their ability to ‘understand’, ‘retain’, ‘use’ and ‘weigh up’ the information given to them for the assessment (Department for Constitutional Affairs, 2007). Autism can impact on how someone ‘understands’ or ‘weighs up’ information and autistic adults may not demonstrate the same emotional response as necrotypical people to some questions about ‘feelings. Thus, in assessing an individual’s ability to ‘retain’ or ‘weigh up’ information, social workers should understand the personal impact of autism on a person’s ability to ‘process’ information and ‘appreciate’ the consequences of the decision to be made. Some autistic adults may present as ‘knowledgeable’ without being able to ‘appreciate’ the full implications of their choices.

In following the time-specific principle of the MAS, social workers also need judgement skills to ascertain the most appropriate time for assessments. Mental capacity fluctuates. The MAS requires assessments to done when people are known to demonstrate their optimal levels of cognitive capacity.

Thus, if an autistic adult is experiencing ‘meltdown’ or ‘shutdown’ this will not be the appropriate time for assessments. However, every attempt should be made to support autistic adults to make their own decision first, before an assessment is conducted. This should include using communication aids to support a person’s understanding, providing accessible information, using ‘autism friendly’ language, involving their carers, giving them time to process the information, and respecting sensory needs during the assessment (NICE, 2018). Social workers are encouraged to draw on the skills and values discussed under the ‘Practice’ section of this Capabilities Statement in this work.

Social workers should:

- Understand the principles and valuesof the MAS and the Liberty Protection Safeguards and their interface with the Care Act 2014 and Mental Health Act 1983

- Assume that autistic adults can maketheir own decisions, and where this doubted, they should maximite the potential for them to demonstrate cognitive capacity

- Document the wishes and values of autistic adults and an assessment of situations that impair their cognitive capacity and how these may be overcome. This plan should be co-produced with the autistic adult

Indicators of health inequalities in autistic people

- Premature mortality: 16 years sooner than the rest of the population. This increases to 30 years for autistic adults with a learning disability (Autistic, 2016). Furthermore ‘The risk of early mortality from all causes among people with autism is nearly twice that of the general population.’ (Mandell, 2018; p. 234)

- Increased mortality: Rate of death for autistic adults with a neurological condition is 40 times higher than the rest of the population. (Autistic, 2016).

- Suicide: An often-cited Swedish study (Histrionism eta al, 2018) found increased deaths from suicide, arising from psychiatric co-occurring conditions and lack of protective factors from social and familial networks

- Eating disorders: There is a recognized association between autism traits and eating disorder. Around 1 in 5 women with anorexia are autistic (Harper eta al, 2019), with worse outcomes than the general population. Often, individuals who are undiagnosed will first present to eating disorder services in a crisis – social workers need to be aware of the significance of this and ensure they are knowledgeable in accessing specialist support.

Autistic people experience barriers to health care. For instance, systems for making appointments are often through telephones and staff may not have training in how autistic people communicate. Sensory needs may also deter people from realizing the pain they are experiencing, or they may be sensitive to touch during a consultation; and the ‘environmental factors’ within waiting rooms and medical consultations, may discourage autistic adults from accessing health services (Autistic, 2016).

Social workers need to understand the entrenched structural inequalities that lead to these health inequalities – for instance Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic groups will experience even more impeded accesses to health services for diagnosing autism and treating co-occurring conditions. Social workers need to understand these persistent inequalities and through advocacy, interagency working, and co-production, assist families to challenge and shift these barriers.

Using listening, assessment, safeguarding, and inter-agency working skills, social workers should understand signs of suicidal ideation and take emergency action, where required. Autistic adults may also not verbalism these thoughts, but suicidal ideation may manifest through their actions and repetitive behaviors. It is essential that social workers support individuals to access support in order to overcome barriers experienced in accessing health care.

Social workers should:

Understand causes and indicators ofhealth inequalities in autistic adults, and how they apply to ethnic minority groups, who face particular forms of discrimination in accessing health and social care services lAssist autistic adults and their carers to reraise their rights enshrined in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and the Care Act 2014 to make their owndecisions and choices in health and social care lChallenge and advocate on behalf of individuals and communities to ensure access to autism friendly health care services

Knowledge and skills in safeguarding

Social workers have a legal and ethical duty to safeguard autistic adults. Due to their sensory needs and preference for their own company; alongside stigma and labeling, it is recognized that autistic adults experience elevate risk of social isolation. This can also increase exposure to financial, sexual, and physical exploitation. (wow.autism.org.UK/ about/communication/social-isolation.asps). An autistic adult may also have specific behaviors which may place them and others at risk – for instance propensity to leave the family home at night; ‘wandering off’ and therefore ‘going missing’. Where an autistic adult does not conform to ‘typical’ social norms, this may place them at risk of arrest or stigma. Autistic adults also experience hate crime (adults whose disability impacts them ‘socially and behaviorally’ are four times more likely to be victims of hate crime). Within family settings, where carers are unable to manage escalating behaviors that challenge them, they may confine an autistic adult to a room, or try to restrain them, for their own safety. The former has medical implications, however, potentially, it could lead to the deprivation of the liberty of the autistic adult. Other forms or risk include (self) medication through alcohol and other drugs as a coping mechanism for bullying and co-occurring mental health issues (Rodessa and Pirri, 2015).

Social workers should understand and assess environmental and institutional risks to autistic adults. 80% of autistic people over age 16 have been bullied or taken advantage of by someone they thought to be a friend, and offense known ‘mate crime’. (wow.merseysidesafeguardingadultsboard. co.uk/mate-crime/) There have been high profile examples of systematic abuse and human rights violations within institutions.

Social workers should know the signs and impact of a range of abuse – for example, criminal exploitation, grooming, cuckooing, modern day slavery, forced marriage, gangs and extremism.

When visiting hospitals or other care provision, social workers must be curious, question practices, spend time listening and observing, and be confident to challenge. Social workers should scrutinise care plans and ensure that autistic adults are not unlawfully being deprived of their liberty.

Making Safeguarding Personal requires safeguarding work to be person-centred and enhances their involvement, choice and control. The goal should be to improve peoples’ quality of life, wellbeing and safety. During safeguarding investigations, social workers must take the time to build relationships based upon trust, and support individuals to share their experiences. Safeguarding concerns cannot be fully assessed in a single visit and outcomes must be based upon the analysis of information from different agencies and carers. Social workers must be prepared to seek out information and at times to ‘think the unthinkable’.

From institutions to community living: the role of the social worker

Social workers were key within the multidisciplinary efforts of deinstitutionalisation and closures of long-stay hospitals in the 1960s – 1990s. The role of social workers in enabling people with disabilities to lead empower, self-determined lives in communities is as important now as it was then.

In 2011, an undercover journalist secretly filmed physical and emotional abuse of adults with learning disabilities and autism at Winterbourne View private hospital. The footage captured of some of the hospital’s most vulnerable patients being repeatedly pinned down, slapped, draggedinto showers while fully clothed, taunted and teased by staff.

In 2019, another Panorama journalist secretlyfilmed a disturbingly similar pattern of abuse at Whorlton Hall in County Durham.A separate 2019 Care Quality Commission(CQC) Review of seclusion found 62 adultsand children, some as young as 11, were being held in isolation, sometimes for years.

The highlighted examples of malpractice and abuse show institutional failures, lack of oversight in commissioning, and practice deficiencies. People should not be in long stay, inadequate, at worst abusive institutions. In working with autistic adults, social workers should therefore ensure that the starting point is accommodation within the community.

Social workers should:

- Understand safeguarding legislation and policy and their local procedureson inter-agency working and investigations

- Understand the interface between the Liberty Protection Safeguards, the Mental Health Act, and criminal justice. Social workers should reviewsafeguarding plans, ensuring that they enhance the liberty of autistic adults; have ‘proportionate’ interventions based on the least restrictive principle, and are consistentwith ‘Making Safeguarding Personal'

- Enhance their skills at assessing, intervening, and reviewing the safetyand suitability of all care and accommodation arrangements for autistic adults in family and institutional settings.

Understanding and applying the law

Social workers require in-depth knowledge of human right legislation and the legal frameworks underpinning their role and they should keep abreast of developments in case law and precedents. At the time of writing, the relevant laws, guidance, and Codes of Practice in England included:

- The Care Act 2014

- The Autism Act 2009

- ‘Statutory guidance for Local Authorities and NHS organisations to support implementation of the Adult Autism Strategy’ (DoH, 2015)

- Mental Health Act 1983 (as amended 2007)

- Mental Capacity Act 2005 and the Mental Capacity (Amendment) Act 2019

- Human Rights Act 1998

- Equality Act 2010

- Children Act 1989

- Children and Families Act 2014

- Children and Social Work Act 2017

- Special educational needs and disability code of practice: 0 to 25 years

The Care Act (2014) is the primary adult social care legislation and taking into account the particular needs of autistic people, the Autism Act (2009) is autism specific. Both legislation and accompanying statutory guidance stipulate that social care assessments of autistic adults must be completed by an assessor who has a good understanding of autism, or they must consult someone who has relevant experience. Consequently, social workers should know about autism, and their legal duties; and they should be skilful at applying the law to practice.

Social workers should:

- Understand the Care Act 2014, the primary legislation in adult social care and its interface with the Mental Capacity Act 2005, the Mental Health Act 1983 (as amended2007), alongside the Autism Act 2009 and accompanying statutory guidance

- Regularly refresh their knowledge of legislation (including case law, new guidance, and regulations)

- Through critical reflection, understandthe interplay between laws, the values, ethics and practices of social work; and how these can be drawn upon to improve the lives of autistic people.

Transition planning for autistic people

Autistic adults involved in the development of this Capabilities Statement explained that they experienced transitions everyday – this could be ‘minor’ occurrences such as moving between activities, or significant life events such transitioning to adulthood, moving homes, hospital admissions, bereavement, or change of social workers. Every transition experience is unique to that individual; thus, support and intervention must be person-centred and strengths-based. Whatever the transition may be, the need for planning is essential. For example, in changes of accommodation, photographs, written descriptions of the new residence, and introductory visits are essential.

For an autistic young person entering adulthood, they may experience changes in their care plans (potential reduction of services) and accommodation; and their services will be managed under the Care Act 2014 instead of the Children Act 1989.

Whether an autistic child was known to Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) or generic children’s social care services can also impact on transition planning. One of the main themes that emerged from the consultations with social workers to develop this Capabilities Statement is gaps in children’s social workers’ understanding of the Care Act 2014. Similarly, adult social workers do not have the requisite understanding of the Children Act 1989. This gap in the knowledge of the respective workforce can impede transition planning, especially where children have been known primarily to CAMHS. Additionally, when children move to adult services, it may be determined that their needs do not meet the threshold for adult services, leaving them unsupported in the community. For some people this change in routine and support can trigger ‘crises.’

Children’s social workers should begin transition planning early, paying attention to national guidance. Furthermore, all social workers should draw on their critical reflection and analytical skills to remain empathetic and understanding of the implications, meaning, and emotional impact of transition from the perspective of autistic adults and their carers.

Social workers should:

- Understand the statutory and practice guidance and legal rights on transitions to adulthood. These include the Children and Families Act 2014 (under which Education, Health and Care Plans must be maintained until the age of 25) and the role of the Care Act 2014 and the Mental Capacity Act 2005 in transition planning

- Understand the practical and emotional impact of transitions and ensure person-centred planning, respecting peoples' right to self-determination

- Advocate for change and improvementwhen the experience of transition between services is inadequate, at individual and systems levels.

Supporting family and friends’ carers

While most carers find caring rewarding and recognise that they have an (inter)dependent relationship with autistic adults that they care for, the role can also be emotionally, physically, and mentally challenging. Carers involved in the development of this Capabilities Statement reported limited access to support and recognition of their entitlement to services. Social workers should be open and honest in their approach, seeking to build effective relationships with carers. This includes seeking their views in any assessments, reviews, care and support planning; and appreciating their expert knowledge about the people they care for. This must however be balanced with the wishes and feelings of the autistic adult. Therefore, using their judgement skills, social workers should maintain a balance between autistic adults’ right to privacy and involvement of carers in assessments and care planning.

Social workers must recognise that carers’ physical and emotional wellbeing and their financial resources are fundamental to their ability to support autistic adults; however, these can be affected by their roles. Carers are entitled to assessments under the Care Act 2014. Support plans should include an analysis of the everyday caring role of carers and identify contingency plans for how this will be met should they no longer be able to fulfil this. Support should also be offered to carers to attain their own life goals.

Social Workers should:

- Understand, apply and promote the law, policy and local arrangements to support carers including the provision of carers, assessments under the Care Act 2014

- Work in partnership with carers to develop trusting relationships based on openness, honesty and transparency

- Provide accessible information about finances, commissioning and decision-making on care planning to carers.

Supporting parenting

Social work with autistic adults can involve supporting them in their role as parents In the consultations to develop this Capabilities Statement, participants who were autistic parents reported encountering stigmatisation and belittling of their parenting skills. They felt this was caused by prejudice, or social workers’ own knowledge gaps on autism. These led to the erosion of their parenting rights.

Notwithstanding their strengths and abilities, autistic adults who are parents experience particular challenges. The birth of a child triggers the involvement of several professionals with different but sometimes overlapping roles in the lives of autistic parents.

This will necessitate several appointments and home visits that must be kept. All new parents can struggle with these new life changes. However autistic people may find this challenging because the involvement of services may lead to disruption of their outines. They may be also be required to socialise with new people in parent groups and they may find this social interaction difficult. Furthermore, the demands of the new baby can clash with the sensory needs of their autistic parents (for instance crying). These can interfere with how autistic parents respond to their child, although they are able and motivated to meet their needs, and it can also impact on their desire to engage with services (Brook, 2017).

In consultations with autistic adults, those who were parents of autistic young people spoke about transition times as being especially difficult. They experience reductions in services. They also have to manage the tension between empowering their young adult children and managing the risks that they face. They said that this may lead to them becoming ‘overprotective’. Supporting autistic parents to young children and adults requires skilful, empathetic, and ethical social work practice. For the reasons discussed under ‘Developing relationship-based approaches’ social workers should seek to minimise the anxieties that autistic parents will experience as a result of their involvement in their lives. Social workers need to be aware of the difficulties parents experience in parenting their autistic son or daughter. Parents can be affected by stereotypes such as ‘parenting stigma’ (in the consultations with autistic adults during the development of this Capabilities Statement, examples given included disapproving looks or unfavourable comments from the public -for example in the supermarket - and lack of understanding from professionals). Parents spoke about how prior to a diagnosis, they were often offered parenting support which was not autism specific.

Social workers need to understand and be able to signpost to services who can offer specialist support. Social workers need to ensure that processes for supporting children are accessible for autistic parents. This may mean thinking differently about home visits, assessments and meetings. The parent should be asked about what their autism means for them and how best to support them.

Social workers should:

- Social workers should understand ‘parental responsibility’ and parentingrights under the Children Act 1989 and human rights legislation on the right to family life

- Take time to understand the impact of autism upon an individual’s parenting and any necessary adjustments

- Identify and provide specialist support, seeking guidance from a specialist as required

Impact

This section of the Capabilities Statement explains the difference that social workers can make to autistic adults through their knowledge, skills, and values, based on the Impact ‘super domain’ of the PCF - ‘How we make a difference and how we know we make a difference. Our ability to bring about change through our practice, through our leadership, through our understanding, our context, and through our overall professionalism.’ (BASW, 2018; p.4). The Impact ‘super domain’ consists of the PCF domains 1 – Professionalism, 8 – Contexts and Organisations, and 9 – Professional Leadership.

Key messages

- With their understanding of the multi-agency context of statutory services,knowledge of social care legislation, and contacts within communities, social workers should: signpost people to services, provide leadership to ensure that care is managed in the community and not hospitals; and they should protect the human rights of autistic adults

- Social workers should understand what causes ‘crises’ for autistic adults, their behaviours during crises, which can be troubling to manage, and how these can be de-escalated. Social workers should understand the personal, environmental, and developmental factors that cause people to express behaviours that are difficult to manage

- Autistic adults prefer to work with social workers with specialist knowledge of autism. Social workers should request autism training, which should be led by an autistic person. Social workers require regular supervision based on models of critical reflection that enable them to integrate theoretical knowledge and practice wisdom.

Professionalism: providing leadership in multi-agency work

Services for autistic adults are provided within specialist autism teams, specialist learning disability services, or generic adult services; sometimes through integrated NHS and local authority services, or separately. Whatever the configuration, care for autistic people is achieved through multi-agency approaches, featuring different professionals from both the statutory and third sector.

Within this context, social workers are relied upon because of their whole systems understanding of peoples’ needs and configuration of services such as housing, welfare benefits, behaviour support, and safeguarding (Boahen, 2016). In multi-agency work, allied professionals’ value social workers’ understanding of the law and human rights, while people who use services treasure the profession’s value base (Manthorpe et al, 2008).

The social work role with autistic adults must include professional leadership. Drawing on their understanding of autism, social workers should signpost people to diagnosis services and arrange post-diagnostic support. Social workers should be able to apply social work knowledge, skills and values to lead a multi-agency team to improve the care and support available to autistic adults. Social workers should also lead within the social work profession demonstrating best practice.

Social workers should:

- lUnderstand the configuration of their local autism services and inter-agency referral protocols and procedures interagency referral protocols (or procedures) and the access points for services

- Work collectively with (self) advocates and fellow professionals services for autistic people

- Develop collective leadership in a multi-agency setting

Preventing and deescalating crises and behaviour that challenges

Autistic adults may experience ‘crises’ when they are distressed and are unable to manage this through their usual coping strategies. This may manifest in problematic behaviours, identified by carers involved in developing this Capabilities Statement as ‘hitting out’, ‘head butting’ or ‘having a meltdown’. Social workers who participated in the consultations (see Methodology section) described crises as ‘anything that creates anxiety or distress’ ranging from unplanned changes to care plans or routine everyday occurrences,and distressing news such as loss of benefits and support services, or changes in family circumstances. Crises also occur when the police become involved because an autistic adult has (mis)interpreted neurotypical norms (DoH, 2015) – for instance personal space boundaries and the differences between platonic and sexual relationships. This may lead to arrest, and encounter with the criminal justice system could be distressing for the autistic person.

Social workers should seek to prevent crises through care planning. This involves updating care plans, keeping accurate and accessible assessments about stressors and triggers, and direct work with autistic adults to identify de-escalating measures. Effective interventions, including mental health, should also be documented on social care records and social workers should advocate and promote least restrictive interventions.

Crises and behaviour that challenges may also be caused by the inability of services and professionals to develop suitable care plans. Current consensus is that behaviour that challenges is caused by a combination of psycho-social, developmental, and environmental factors:

‘[it] is more likely to occur in environments that are poorly organised and unable to respond well to the needs of the person. There is often a mismatch between the needs of [autistic] people with intellectual disabilities and the range of available, individualised packages of support that can respond to behavioural challenges.’ (Royal College of Psychiatry, 2016; p.9)

Drawing on social model approaches, social workers should engage with autistic adults and their carers to understand their triggers and care plans aimed at preventing these behaviours from arising should be co-produced with autistic adults and their family, friends and carers. Where people are experiencing mental distress, social workers should note that

‘Compulsory treatment in a hospital setting is rarely likely to be helpful for a person with autism, who may be very distressed by even minor changes in routine and is likely to find detention in hospital anxiety provoking. Sensitive, person-centred support in a familiar setting will usually be more helpful.’ (Mental Health Act 1983: Code of Practice (DoH, 2018; p. 209))

Values underpinning social work and behavior that challenges

Quality of life: following principles of personalisation, care plans should seek to maximise quality of life

Safeguarding: people should be encouraged to take positive risks and their right to ‘unwise’ decision-making should be respected. However, the first principle is safeguarding them

Choice and control: people should have control of their services – this can be achieved through co-production and partnershipsLeast restrictive interventions: this should be the starting point for all interventions (including restraining people for their safety)

Equitable outcomes: social work should address the health and social inequalities that may cause people to display behaviour that challenges

Adapted from Association of Directors of Adult Social Services,Local Government Association, NHS England (2015)

Social workers should:

- Ensure that care plans follow the guidelines in ‘Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges’ (NICE, 2015)

- Be guided by the principle of prevention,social workers should work with autistic adults and their carers to prevent crises and/or behaviour that challenges

- Have a detailed Crisis Plan, includingrelevant information, de-escalation strategies, and knowledge of professional and social support.

Being responsible for self and ongoing learning

There is a recognised knowledge gap in social workers’ understanding of autism. Autistic adults who participated in the development of this Capabilities Statement reported that social workers who do not have knowledge of autism and/or engage in regular CPD may be ‘dangerous’ to them having their needs met. Thus regular CPD activities to improve knowledge and skills in autism is one key component of professionalism in social work with autistic adults. A second strand involves social workers fulfilling their professional duties – for instance managing their workload, completing tasks as requested and advising where this is not possible; andmeeting the expected standards of values and professionalism. Social work with autistic adults can be immensely rewarding, however it is also challenging. Consequently, professionals should seek regular supervision and allocate time for their CPD. This is essential for professional practice, for registration and for maintenance of wellbeing and resilience in the workplace. They should also maintain accountability to The Code of

Ethics for Social Work (BASW, 2014). On the part of employers and Practice Leaders, they should support social workers as stipulated, respectively, in the Standards for Employers of Social Workers (Local Government Association n.d) and Post-qualifying Standards for Social Work Practice Supervisors in Adult Social Care (Department of Health and Social Care, 2018).

Social workers should:

- Seek and prepare for regular practice supervision

- Engage in critical reflection to understand the power inherent in their role and how this can be deployed alongside people to empower them

- Honestly and regularly appraise theircapabilities. This iincludes identifyinggaps and planning CPD to address these.